This feature is a part of "The Dotted Line" series, which takes an in-depth look at the complex legal landscape of the construction industry. To view the entire series, click here.

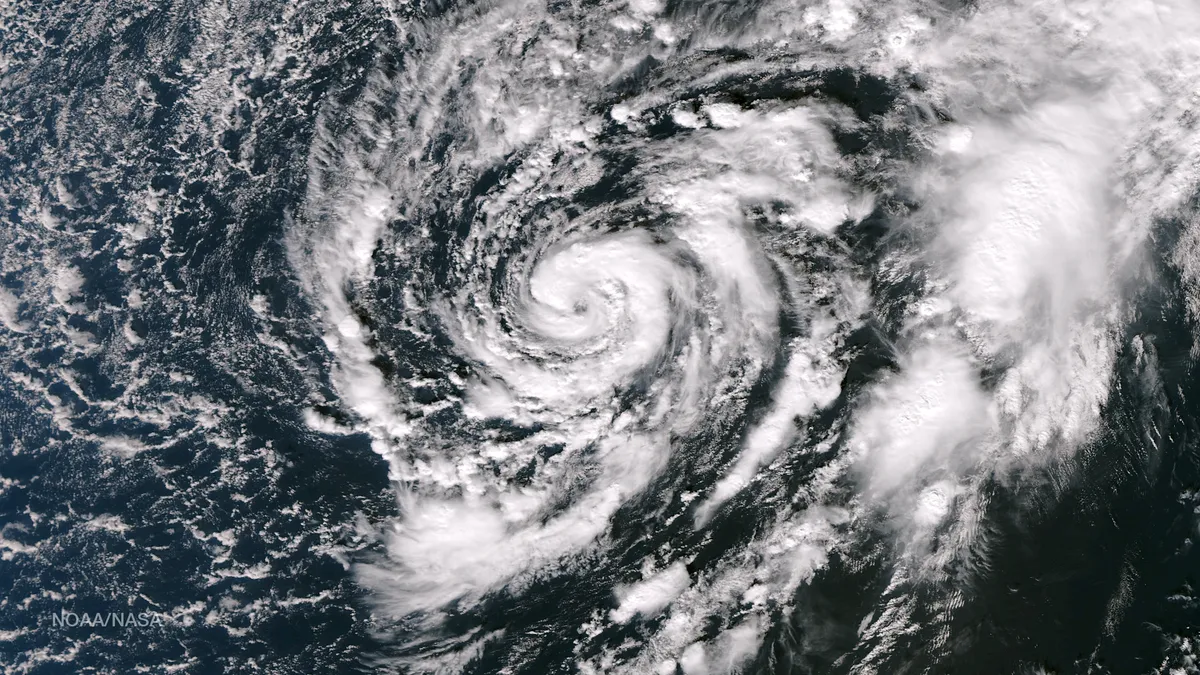

So far this summer, the United States has seen what many would consider to be more than its fair share of natural disasters. Hurricane Harvey made landfall in Houston on August 25 causing an estimated $198 billion in property damage. Less than two weeks later, Hurricane Irma made its way through Florida and into the Southeast, leaving a up to $100 billion in damage in its wake.

The onslaught of storms didn't stop there, however. As insurers began their assessments and construction crews began rebuilding efforts, the Gulf Coast and the country's island territories braced for further impact. Occurring nearly in tandem with Hurricane Irma, Hurricane Maria made landfall and decimated Puerto Rico in September, leaving the majority of the U.S. territory without power. That bill could reach reach $95 billion. Earlier this month, Hurricane Nate, a relatively smaller storm, battered Mississippi, resulting in a projected $500 million in damage.

While damage from those storms has been extensive, the nation's natural disasters and the damage caused by them has not been confined to the South. In California, wildfires have ravaged more than 220,000 acres of picturesque vineyards and farmland, as well as residential and commercial properties. The fires, still ongoing, are expected to result in at least $65 billion in damages, CNN Money reported.

Insurers estimate that claims for this year’s hurricane season alone will reach $100 billion, and contractors are sure to be kept busy with rebuilding work for the months and years following these events. The pace of progress is expected to be even slower given the industry's widespread labor shortage.

Many construction companies, however, will explore opportunities with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and seek to enter into contracts with the agency for work that insurance doesn't cover — a strategy, the organization said, would be ill-advised.

FEMA does not enter into direct contracts with construction companies to rebuild homes or commercial properties. The agency, according to Joseph Moore, an attorney and partner at Hanson Bridgett, provides monetary relief in the aftermath of natural disasters through grants and loans. It is then up to the business or homeowner to seek out a contractor.

But contractors do need to know about the conditions that come along with FEMA money. Even though their contracts might be with private homeowners or a public owner like a school, the use of that money is still governed by FEMA rules — and misunderstandings can cost construction companies heavily.

Under FEMA’s Individuals and Households Program (IHP), the agency will provide up to $33,000 in disaster assistance, which includes money for home repairs that the homeowner's insurance doesn't cover. If the homeowner still needs additional money, they can apply for Small Business Administration loans.

However, by giving this type of grant to a homeowner, FEMA intends to bring the home to a safe and sanitary condition, not to pay for a full restoration. As a result, when a contractor enters into a contract with a homeowner who has a financial commitment from FEMA, it's vital to check the scope of work outlined in the contract with that owner to ensure they understand what reimbursements to expect from FEMA.

A FEMA grant, for instance, might be enough to cover the purchase of basic flooring like laminate or vinyl tile, but not the hardwood flooring that was ruined in the disaster. That can be an important distinction for the contractor to know before performing change order work for more than what the homeowner can expect to receive from FEMA.

With commercial property repairs, however, there are a different set of challenges owners must face. And none of those, like federal residential disaster options, will result in a direct construction contract with FEMA.

"Doing a job that ultimately qualifies for a FEMA grant carries the security that funding will be available. If a contract is approved for a FEMA grant, the contractor can feel secure that it will be paid"

Joseph Moore

Attorney and partner at Hanson Bridgett

"When it comes to contracting, generally speaking," said Jimmy Christianson, regulatory counsel for the Associated General Contractors of America, "FEMA is not your owner. FEMA generally grants money to state and local agencies who grant money to public and private entities to repair or rebuild." FEMA rules apply to how those dollars may be used, he said, but the agency is not managing the projects that receive the money. In fact, Moore said, FEMA hires third-party inspectors who authorize reimbursements.

FEMA commercial loans and grants have restrictions similar to those of residential loans in that the goal is to bring the structure in question back to a functional, safe level. However, given that most contractors want to make their owners happy, Christianson said, they might choose to proceed with work without knowing if that work qualifies for reimbursement or realizing there are restrictions in the first place.

"You have to understand what FEMA will and will not pay for and make sure that, if your owner doesn't know, then you know," he said.

As for a construction company's contract with private owners, Moore said, those are traditional contracts. It's the owner's reimbursement requirements that have the potential to turn that arrangement on its head.

"Doing a job that ultimately qualifies for a FEMA grant," Moore said, "carries the security that funding will be available. If a contract is approved for a FEMA grant, the contractor can feel secure that it will be paid."

Still, because payment will include federal funds, the contractor must comply with the Truth In Negotiations Act and account costs and expenses. "This could require an added amount of administrative expenses, and contractors not familiar with public contracting projects might not be accustomed to such requirements," Moore said.

The same holds true for contractors pursuing commercial repair work or public work like highway repairs, although contractors who have already provided past services to state agencies are more likely to be familiar with these rules.

Christianson said contractors would do well to have a discussion about what FEMA will and will not cover with the owner before executing a contract. Contractors, he said, should also look to inserting language into the agreement that would require owners to pay for any expenses FEMA doesn't approve.

"Whether the owner will sign something like that is another question," he said.