Brian Krause knows that when it comes to actually building what’s in the 3D model of his latest commercial construction project, his best-laid plans can be foiled by something as seemingly insignificant as a 1/4-inch bathroom tile.

That’s the lesson Krause, vice president of the virtual design and construction team at Bethesda, Maryland-based Clark Construction Group, has taken away from the convergence of technology happening in construction.

“Things can look right in the model, but once all the materiality comes in, they may not be right in the field,” Krause said.

Take, for instance, the typical building code clearance requirements for setting a toilet flange 18 inches from the side walls in a commercial space to comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

"A designer can model that toilet flange 18 inches off the wall,” Krause said. “But the ceramic tile you finish the wall with may add a quarter of an inch. So when the inspector comes out and pulls the tape at 17 and ¾ inches, he’s going to say that you don’t meet code. That’s the kind of check that has to happen in the model today.”

To create that check, Krause is seeking a construction worker to fill a job that only recently emerged in the industry: a computational engineer.

“That’s someone who can interrogate the data in the model, to make sure it’s right,” Krause said. “That position didn’t even really exist until a few years ago, and for a lot of firms, that position still doesn’t exist today.”

A new tech job looking for workers

For Krause and other tech-savvy managers, there’s a new shortage of skills in construction, but it’s not concentrated in any one trade. Instead, construction tech leaders are looking for people who understand construction’s emerging technology stack, as well as how the built environment works, to better address perennial pain points and help actual tradespeople work better, faster and more efficiently in the field.

“Finding the mix of computational knowledge, mixed with construction tech and building knowledge, is a formula you don’t typically see,” Krause said.

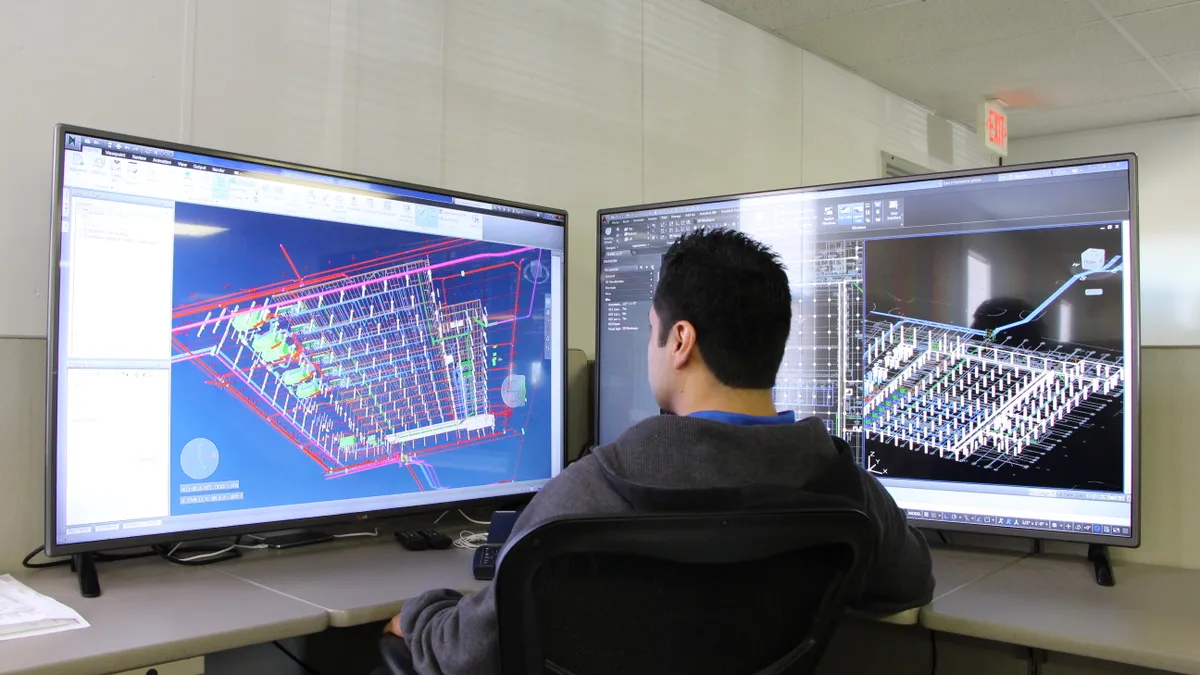

And yet, as construction goes kicking and screaming into using technology at a more fundamental level — from 3D BIM modeling at the design stage to scheduling and project management in the field and reality capture devices that confirm everything’s on track — construction firms are increasingly looking to tie all those different applications together. Once they do, they’re trying to leverage the data that’s generated from them, even as harnessing and organizing that information is becoming a tougher ask.

“The hardest skill set to pick up is that solutions architecture,” said Anita Woolley Nelson, chief strategy officer at Skanska USA Building.

Finding technology workers who understand how construction’s emerging tech stack works together is one of her biggest challenges.

“It’s really about understanding data, how it moves, and how systems talk to each other,” Woolley Nelson said. “Everyone from Procore to Autodesk are constantly evolving their suite of products, so understanding those products and providers is really becoming a new skill set in and of itself.”

Tech flows downhill

Matt Abeles, vice president of construction technology and innovation at Washington, D.C.-based trade group Associated Builders and Contractors, agrees that just being able to keep all the technology straight is becoming a sought-after skill in construction.

“Construction technology is a very crowded market,” Abeles says. “There’s a lot to choose from, and it’s an endeavor in itself to understand and weed through what’s good, what’s bad and even more than that, what works for your business.”

Given that landscape, roles that used to focus mostly on building and construction have become increasingly tech oriented.

“Our associate project managers are really having to learn how to use all the different software together, and how to leverage it, because the databases are just becoming bigger and bigger,” said Kar Ho, virtual design and construction manager at Current Builders, based in Pompano Beach, Florida. “If you look at something like Procore, that’s not just project management anymore. It’s the accounting, and the BIM that’s on there as well. You have to be able to adapt to manage that large of a database, and operate within that environment.”

At Young Harris, Georgia-based Compass Creek Consulting, which works in pipeline construction, CEO Donna L. McCluskey says having the ability to tie all the different field technologies together, while processing data on site, is quickly becoming a must-have to compete for jobs.

“It’s really that background where we can bring in that integrated technology,” McCluskey said. “All of our clients are looking for mobile applications that work on the fly, and being able to process information quickly to get away from the old fashioned pen and paper method.”

Getting at the data behind the programs

Of course, 3D BIM models and digital twins can make design more efficient while flagging constructability issues earlier. And project management software can tie it all come together more smoothly in the field.

But the real power of those types of programs, which will allow construction to shed its mantle of being a productivity laggard over the last 50 years, is the potential to not have to constantly re-invent the wheel with each new project.

“Benchmarking and understanding cost on projects is a very simple area where you can take historical data from estimates compared to the actual cost,” Woolley Nelson said. “If you can do that, you can demonstrate to a client what a certain trade might run you for a certain size project in a certain location. That’s what’s really going to change the game.”

But you have to capture all that data first, and doing so isn’t easy, even for people who know how. More challenging still is finding an individual with those skills who also understands the construction process. Finally, there’s the fact that construction firms aren’t the only ones chasing workers who can make sense of the data for them.

Take Krause at Clark Construction. In order to find constructability and building code compliance issues in his 3D models before they become problems in the field, he needs computational engineers who can write computer script and algorithms to comb his plans via automation, instead of having a trained design professional do it manually.

But while he feels he can teach VDC skills to builders, and building skills to technology-minded professionals, when it comes to data-oriented coders, he’s not the only hiring manager looking for those capabilities.

“The coding side is a little bit tougher because most people that are going to school for that want to work for Apple or Google,” Krause said. “It’s not in their mindset to come to a construction company.”

Skanska faces the same challenge.

“We're competing with the Facebooks and the Amazons of the world for people who really understand data,” Woolley Nelson said.

A growing demand trend

For Abeles, attracting that type of talent to the construction is becoming a make-or-break moment for the industry, if only because technology is now becoming more widespread beyond the top tier firms.

“The bigger contractors are the ones who typically have chief innovation officers,” Abeles said. “But what you're seeing is that type of role coming to the small and mid-sized contractors now because of the need for tech, too. And what a lot of them are learning is it’s not enough to have your I.T. guy be your construction tech guy. The guy who's fixing your computer does not know how to deploy a project management solution.”

Instead, at Clark, Krause is still looking for that perfect fit of employee who has a top-to-bottom understanding of the ever-changing world of construction tech, the principles of good construction and project management and computer coding, all wrapped into one.

“It's someone who knows how to do coding, and they also know something about building and construction, and then they know something about construction tech,” Krause says. “That’s a hard mix to find.”