This is this second article in our series on young professionals in construction. Read more here.

In the first installment of our new series, The Future of the Field, we introduced you to a young professional just a few months into her first full-time job in the field: 23-year-old Kristy Thompson, who works as a site superintendent for a small custom homebuilder in Greer, SC.

For our second post, we’re looking to the other end of the spectrum to see how young professionals are handling company leadership, implementing technology into project workflows and eyeing the generation after them.

Meet architect Charles Hendricks, 43, a partner at The Gaines Group Architects in Charlottesville and Harrisonburg, VA. The firm, which was founded in 1987, specializes in sustainable construction, earning accolades from the U.S. Green Building Council as the best small architecture firm in 2014, and from the National Association of Home Builders as a finalist for its Best in Green Young Professional of the Year Award in 2015. The firm has been recognized by the Virginia Sustainable Building Network as well as the state’s Governor’s office for green leadership.

In 2013, Hendricks was named to Engineering News Record's Top 20 under 40 ranking for the Mid-Atlantic region.

But when you ask Hendricks what keeps him busiest, it’s not architecture but life outside the office. In addition to his family, Hendricks is involved in industry groups including the Shenandoah Valley Partnership's Development Committee, the Shenandoah Valley Builders Association Education Committee and the Central Virginia chapter of the Construction Specifications Institute.

We talked with Charles about how he came to be an architect, what issues the industry faces today and where he sees it headed.

Editor's note: This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

When did you know you wanted to be an architect?

Seventh grade. I took a drafting class and it clicked for me. I’m dyslexic. School didn’t come very easy to me — ever — it was always a struggle and back then not many teachers knew how to deal with somebody that was dyslexic. The visual process that is architecture, being able to get a design problem and solve it visually based on proportions and aesthetics, works really well with how my brain is wired.

What was your first job in the industry?

My first paying job was working at this firm that I now own. I started as an architectural intern in 1999, so I did a lot of drafting. Back in high school, I worked for the company that is now AECOM in Roanoke, VA. I did a high school internship in a dark basement with the CAD guys.

How did you go from intern to partner?

I had graduated from University of Virginia with a Bachelor of Science in architecture. When I started at Gaines, I was mainly a drafter doing details, drawings, corrections — and learning. I quickly grew to be a project manager for a lot of our custom residential jobs. Over the first three years at the firm, I was learning everything about how the firm works, how architects work with clients and how buildings go together. I left the firm and went to graduate school at the University of Tennessee to learn more about sustainable design. When I graduated in 2003, I spoke with [founding partner] Ray [Gaines] about returning to the firm, finishing my internship and getting licensed.

While going through that process, I was project managing multiple jobs for both residential and commercial projects. I started finding and securing my own clients. When I earned my license I was offered partnership — nine years ago now — and opened the Harrisonburg branch of our firm.

What types of projects is your firm doing now?

We do everything from kitchen and bathroom rehabs to residential additions to full-custom residential design. The smallest house we’ve done in the last few years was 358 square feet, and the largest one we’ve done recently was just under 11,000 square feet. That’s a pretty wide range, but most of our houses tend to be in the 2,000-to-4,000-square-foot range.

Can an 11,000-square-foot house be sustainable?

That’s a good debate happening in the sustainability world. This particular house is super-insulated. It used local and reclaimed materials, low- or no-VOC paints and has solar panels on two roofs. It’s not zero-energy but it's low energy, supplying its own off the roof. It definitely has green aspects to it and that’s what [the clients] wanted. If this is their forever home, then I would say that’s a sustainable strategy. But this discussion is broader than one house.

What are some of the biggest challenges facing small design practices today, including your own?

In our area, the biggest challenge I face is the lack of design. I am one of the only firms in my market that provides residential design services. I compete against builders and drafters that offer plan services, not design services. Many clients don't understand the value-added differences between the two. The idea of paying more up front to save more during construction is hard to quantify and requires a higher level of trust. In other areas of the country, the idea of paying for design comes easier.

What systems and materials do you use to accomplish your firm’s sustainability work?

Our goal in sustainability is to design healthy, energy-efficient, durable solutions that are affordable. If it’s not affordable, it’s not sustainable. We do a lot of work to understand building science, from materials to methods. Understanding the balance between innovative new strategies, “the way we’ve always done it,” and how to put all the pieces together helps us make the house a system. A house or building is the most complicated machine many people will ever own or operate. But many people don’t look at it as a machine.

We use the same strategy with materials — things that are healthy, durable, that don’t off-gas, that will last a long time. Most of the materials we use are tested, mainstream. We use photovoltaics on a lot of our projects, solar thermal, evacuated tubes, flat-panel collectors. We also incorporate products and systems including metal roofs, cementitious siding, insulated concrete walls, reclaimed wood flooring, no- or low-VOC paints and stains, recycled-content products, low flow fixtures, mini-split ductless HVAC systems, high-efficiency heat pumps, heat pump water heaters, Trombe walls and spray-foam insulation.

How did you discover your passion for your particular type of architecture?

After I finished undergrad at UVA, I heard a lecture by Samuel Mockbee, an architect and the co-founder of the Rural Studio program at Auburn University [in Hale County, AL]. They made movie about it: Citizen Architect: Samuel Mockbee and the Spirit of the Rural Studio (2010). He talked about the power of using design to help others and change the world. Hearing that architecture wasn’t just a job of sitting down and drafting and drawing a house and solving these design problems, but instead taking your skills and the knowledge and improving other peoples’ lives — that’s why I do sustainability. Samuel Mockbee is one of my idols. That lecture changed my life.

What should the industry be doing differently in terms of sustainability and building in general?

A lot of people are scared to change things in our industry. They say, “That’s the way we always do it.” That voice is very strong in our industry. To change this, we need to increase our communication. That’s why I’m a member of the Construction Specifications Institute. It’s the one organization in the industry that brings everyone to the table as an equal — product representative, architect, engineer, specifier, contractor.

We often see each other as adversaries, specifically in the architecture world. I do compete with other firms for jobs but, hopefully, each of us understands that the right jobs for us will come along. There’s a generation in leadership roles in the industry who don’t want to collaborate with other architecture firms. They see them as competition and hold their secrets tight.

What role do age and experience play in the industry today?

There’s a whole generation missing in front of me that would be in leadership roles right now. I’m 43 and the 50-plus-year-olds aren’t there. My two partners are in their 60s. A lot of those people who are in their 50s today left the industry during the financial downturn.

When I interview people to work for me, I only want people who want my job. I want to retire. I think that’s different from my partners’ generation. I don’t want to work until I die on my drafting board. I want to continue doing design because I love it, I just don’t want to have to bill for it. I want to work for the people who can’t afford to hire me now – non-profits, low-income projects. There’s huge potential to help people.

What’s next?

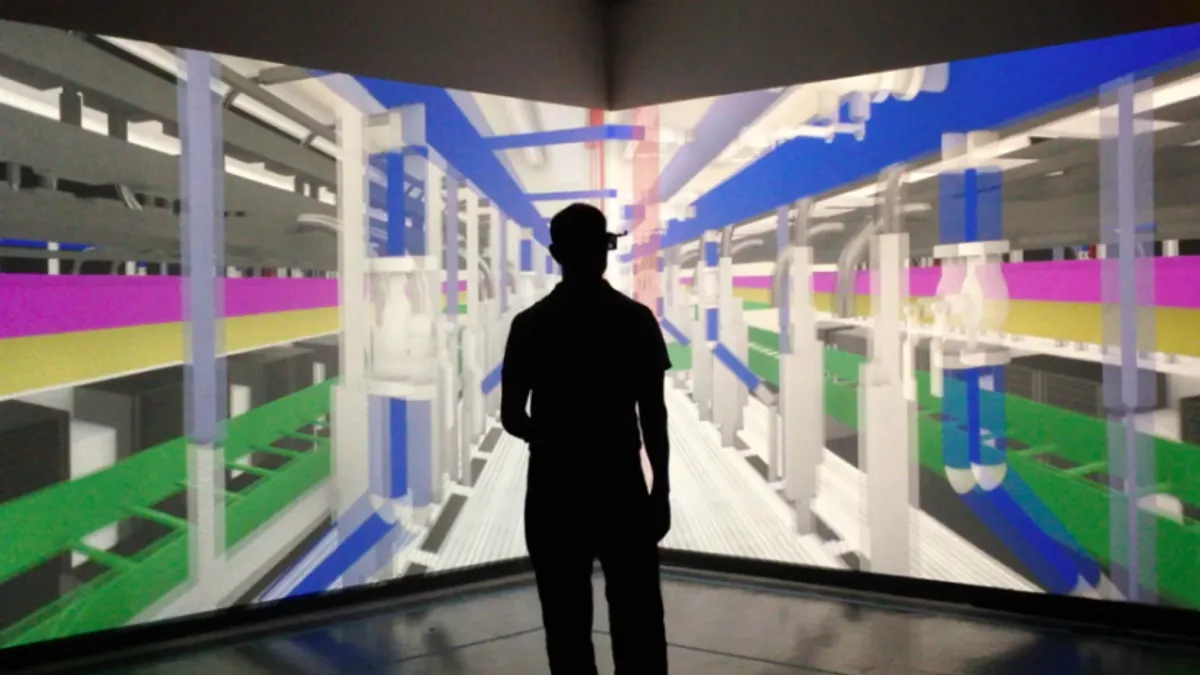

Most of my staff is younger than I am. I’m looking at that next generation to lead us in new directions. New technologies like BIM, 3-D printing and virtual reality — these are things that are going to be in the industry before I’m ready to retire. I need people who are experts at that coming in, and I’m going to reward them because I’ll need them to evolve the business.

There has been an issue with bringing younger people, minorities and women into an industry that’s mainly dominated by white males. But I see that changing. Some of the more talented designers I see fit all those categories. The middle-aged white male is not the innovator anymore.