For years, Jaime Rivera faced obstacles to stable work opportunities as a result of his criminal record. A recent graduate of the Rebuilding Reentrants & Reading program, Rivera (above right) said he was grateful for a second chance.

"If it wasn't for the program I'd probably still be out there getting crap jobs," Rivera said. Now, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, where many have lost their jobs or found their income impacted, Rivera has had stability at his job in Reading, Pennsylvania.

April — dubbed "Second Chance Month" — is dedicated to raising awareness about the barriers formerly incarcerated individuals face when reentering the workforce and helping them find a brighter future.

In recent years, the construction industry has faced an employment crisis. Construction companies will need to hire at least 430,000 more workers this year than they employed in 2020, according to an analysis of U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data by Associated Builders and Contractors.

Contracting groups and employers are attempting to find the middle ground between those issues, by training new workers with criminal records, in an effort to provide them a second chance, and increase the number of skilled workers on the jobsite.

Skill building

The ABC Keystone Chapter, located in Manheim, Pennsylvania, is the registered apprenticeship sponsor and partner for Berks Connections/Pretrial Services located in Reading, Pennsylvania. BCPS's R3 program — which Rivera went through — is designed to give people with a criminal history the opportunity to acquire skills in the construction trades that lead to employment and access to projects, like renovations of some of the city's neighborhoods.

During the eight-week training program, students receive a gradually increasing weekly stipend, a total of $2,000 upon graduation with a perfect record. As part of R3, students get additional cognitive training to help them with rapid decision-making, Peggy Kershner, co-executive director of BCPS, told Construction Dive. The class is intended to help students identify triggers and find positive solutions when an issue may escalate on the jobsite or in the broader world.

The cognitive training, hands-on work such as fixing dilapidated houses with Habitat for Humanity and the payment for enrolling in the course motivates workers to choose construction, Kershner said.

Programs for reentering citizens offer a way to develop their hard skills — such as tradesworker certifications — and to beef up their life skills designed to help overcome societal obstacles, according to Kristen Rantanen, senior vice president of communications and public affairs for JEVS Human Services, a social services organization in Philadelphia that has helped reentering workers find jobs in construction. The key is to recognize the experiences and skills returning citizens can bring to employers, Rantanen says. JEVS also provides reentering workers with basic needs such as housing, food security and aid with physical and mental health.

As contracting groups don't always have the tools needed for fully equipping reentering workers, the best thing they can do to help is partner with established groups, David Helveston, president of the Pelican Chapter of Associated Builders and Contractors, told Construction Dive.

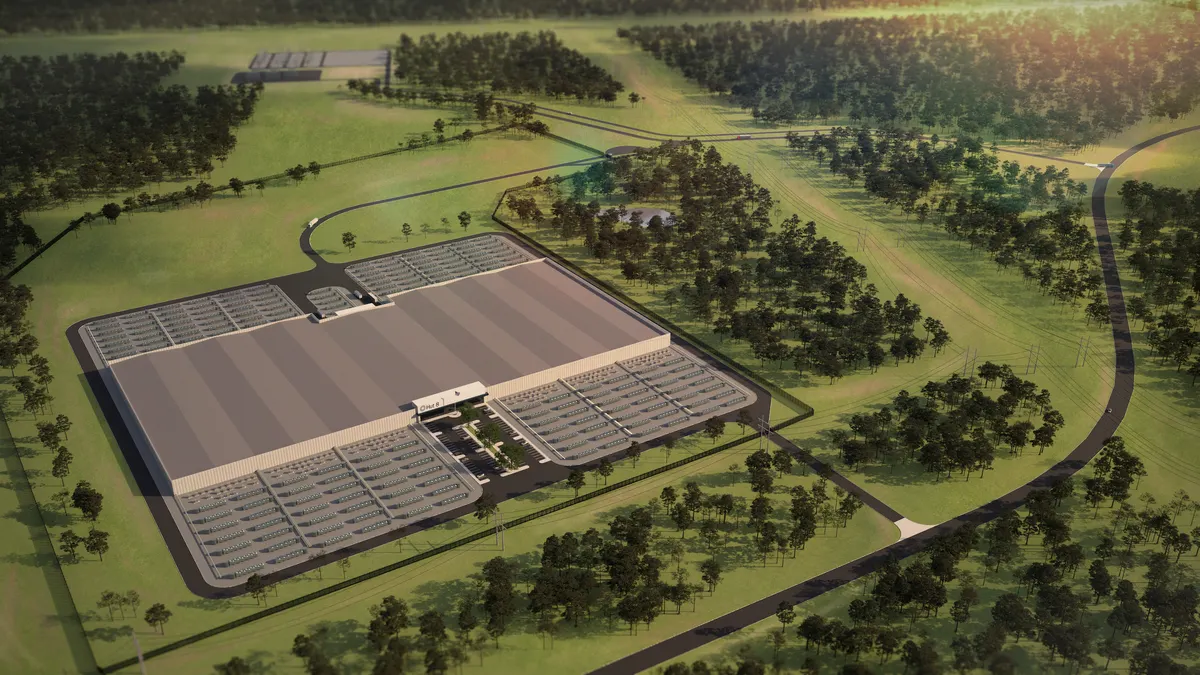

For more than 15 years the Pelican Chapter, which is located in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, has partnered with job reentry programs and churches that offer private funds to assist those looking to upskill. In that time, the partnerships have given almost 400 citizens between the ages of 17 and 35 the chance to learn marketable skills and find employment, after rehabilitation for drug addiction or behavior issues.

The Pelican Chapter does the training, Helveston said, offering "one-off" programs to help potential workers get started before they introduce them into traditional trade programs.

Benefits and challenges

The benefits to employing previously incarcerated employees are many. Returning citizens provide a pool of eager workers, often with prior work histories that can be an asset to employers, Rantanen said. Additionally, the federal government and many states and other jurisdictions offer incentives like tax credits, such as the federal Work Opportunity Tax Credit to employers who hire, train and retain returning citizens.

The benefits for workers are abundant as well. For employees with a criminal past, construction can be a great option due to the daily chance to prove oneself. Bias and stigma are the biggest stumbling blocks toward reentering citizens finding a job, Rantanen said.

"There is often a stigma attached, unfortunately," Helveston said. "But the good news is, much of the construction industry, if you show up on time, you work hard, you'll be accepted relatively quickly."

The responsibility for ending that stigma, however, rests on the employer's shoulders, said Kathleen Stone, employment development specialist for BCPS.

"What you allow to grow, grows. What you don't allow, doesn't grow," Stone said. "A worker focused on getting the job done squashes any stigma."

Stone added that the biggest challenge to getting workers long-lasting jobs is often transportation, as many don't have cars or driver's licenses, and public transportation won't get them close to the jobsite. Groups like BCPS will often coordinate with employers to try to find ways to get a coworker to drive them, or provide other transportation.

Many reentering citizens know that finding a stable job is critical to avoiding recidivism, even though doing so is a challenge. As a result, those that get a second chance often have an overwhelming sense of their loyalty to their employer, Helveston said. Rivera echoed the sentiment.

"Loyalty for my employer is beyond just job-related," he said. "I'd do anything — I'd move a couch for him for free. Anything."

A second chance

Rivera said the best piece of advice he can give to reentering workers is to stick with jobs or programs for the long haul — as most of the money they'd make would come after months of hard work. To help them stay in it for the long haul, groups like BCPS offer retention support, regularly meeting with workers and contractors to keep them employed.

The program he went through is intensive, and requires a lot of hands-on accountability to succeed, Kershner said. Nevertheless, about three-fourths of R3 graduates maintain stable employment and 93% have not returned to jail or prison, according to the program's site.

"I hope people don't define people by the worst decision they made in their life or the worst day in their life," Kershner said. "We're all human. We've all made mistakes."