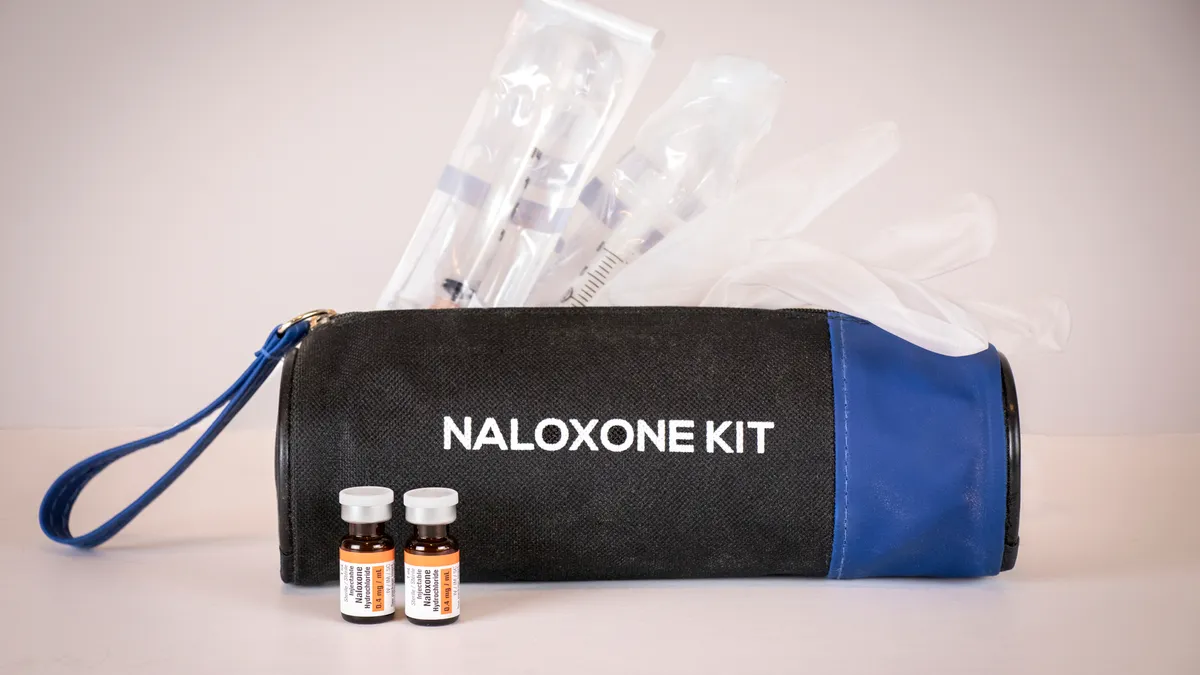

As of June 1, legislation in Ontario, Canada, required every construction site there to have a naloxone kit. The medication, often known by the brand name Narcan, can temporarily reverse the effects of opioid overdose, and provide a bridge until an affected person can receive medical help.

Opioid use disorder has hit the construction industry hard: It has higher rates of overdose death than most other sectors. Providing life-saving medication on jobsites, and educating about opioid use in the industry is now becoming more standard in the U.S. as well as Canada.

“It’s an amazing medication that reverses imminent death. There’s no reason not to have it,” said Chris Trahan Cain, executive director of Silver Spring, Maryland-based CPWR — the Center for Construction and Research Training.

Opioid use disorder has affected Americans in every walk of life, but it’s especially prevalent in construction. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 107,622 people died of drug overdoses in the U.S. in 2021, up nearly 15% from 2020. The CDC also found that overdose deaths involving opioids increased from an estimated 70,029 in 2020 to 80,816 in 2021.

Construction workers are at a greater risk. Studies in both Massachusetts and Ohio show that they are seven times more likely to die of opioid-related overdoses than the average worker.

“There are a lot of things about construction that don’t necessarily lead to a balanced lifestyle,” said Cain, including lack of paid sick leave, non-traditional work schedules and a high number of soft tissue injuries.

“We continuously see doctors prescribe opioids for pain in construction workers when it’s probably not the best pain medicine,” she said. Even though legally prescribed, these prescriptions can lead to addiction, as someone can “become dependent on prescribed opioids in a few days.”

Part of the jobsite’s first aid kit

Although no U.S. state has mandated naloxone kits on jobsites, many general contractors have enacted the practice anyway, with help from public health resources.

In 2017, based on findings of high opioid overdoses in the construction industry, the Delaware Division of Public Health started putting together a construction-specific plan to tackle opioid use disorder and overdose within the industry. Employer tool kits from the division can help people spot signs of opioid use disorder, give information about the epidemic and also provide training and access to naloxone, said Candace Brady, Delaware’s naloxone program coordinator at the Office of Health Crisis Response.

Her team also holds trainings on how to use the medication, presents their tool kit at jobsite safety meetings and sets up tables on jobsites with Dunkin’ Donuts, so they can “interact with some of the construction workers,” she said. “The willingness to be part of this program is there.”

So far, they’ve distributed 354 kits. Employers don’t have to report back, so she doesn’t have statistics on if kits have been used, but she knows the partner restaurant program has utilized the kits.

Brady hopes that how to use naloxone will be seen as just another thing that someone would learn to save a life.

“You’re not just going to walk by someone on the side of the road if they need CPR. You’re just going to do it,” she said. Likewise, this kind of training “needs to be more normalized.”

Adding naloxone kits to a hard hat order

In 2018, Shawmut Design and Construction started their own education about opioid use disorder when they invited a speaker from Grayken Center for Addiction at the Boston Medical Center to give a keynote address to the company.

“It really opened our eyes,” said Shaun Carvalho, chief safety officer at Shawmut. Workers responded by saying “that was a great talk, but what can we now do about it?” he recalled.

That led the company to start a pilot program to see how to obtain an adequate supply of naloxone for their jobsites and train workers on how to use it. It was so successful that now managers can order naloxone in the same way that they’d also order hardhats, safety signage and Automated External Defibrillators (AED) machines. It’s not mandatory on every jobsite, Carvalho added. They leave that up to the discretion of project teams.

Shawmut has also trained all frontline people on their jobsites on how to deploy naloxone, and provides training throughout the year as part of general safety training.

“The more that we can talk about these things as though they’re just as much of a hazard as falling or electricity, they become part of the normal conversation,” Carvalho said. A worker may not overdose on a jobsite, but they may realize they’re on a slippery slope and need to reach out to someone for help, which can help the worker and prevent an overdose in the first place, he said.

Carvalho said no jobsite has had to use the naloxone yet, but they haven’t had to use AED machines either. That doesn’t mean they’re not necessary. Even if not used, they increase workers’ feelings of safety on the job.

“We just need to protect everybody. That’s the approach we go back to,” he said.