Construction of oil and gas pipelines has always been a contentious issue for environmental groups. One of the most high-profile instances involved the 800-mile Trans-Alaska Pipeline System, also known as the Alyeska pipeline, which broke ground in the mid-1970s and was, in large part, a response to the 1973 oil crisis. More than 17 billion barrels later, there hasn’t been the pipeline disaster that critics predicted, but other pipeline accidents have continued to plague the sector and draw controversy.

Most recently, a similar furor has erupted over newer initiatives like the Dakota Access Pipeline. Objections to its path near the Standing Rock Sioux reservation recently drew protesters from all over the country to North Dakota, stalling the project under the weight of legal challenges and predictions about the damage to the environment that a pipeline disruption could cause. During the first days of President Donald Trump’s presidency, however, he signed an executive order directing the expedient review and approval of that project, and it will likely proceed.

While the focus on pipelines has been more on the potential post-construction consequences, there hasn't been much attention paid to the construction process itself. Most onlookers know it’s expensive, and they know it gets oil or natural gas from point A to point B. But what else is there to pipeline construction? It involves lengthy route and review processes, and faces a challenge common to the broader industry — a lack of skilled labor.

Route selection

First and foremost, pipeline construction is all about permitting and environmental reviews, and that starts with planning a route.

"Route selection is a difficult process," said attorney Daniel Deeb, partner at Schiff Hardin in Chicago. "Because of permitting, they have to develop alternative routes."

It usually comes down to "the path of least resistance," he said, meaning that the most beneficial route to the oil company sometimes gets sacrificed for the one farther away from natural resources, endangered species, special geographical features or anything else that could kick up a controversy.

Sometimes the solution is to use an existing rail or other corridor that has already passed federal agency review. Whatever the strategy, in the case of pipeline construction, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission has the last word on geography and issues the coveted permits.

The review process

Before that project milestone can be achieved, though, comes the environmental review process, and to call it lengthy would be an understatement. Assessments and impact statements can take years to complete, according to Deeb. The most difficult part, however, could be the portion of the review that requires project officials to evaluate and include the scenario of no project at all, an option FERC could determine is the best way to go.

If all the paperwork is complete and FERC comes back with a request for additional studies, that could be the agency’s roundabout way of saying the company might need to tray again another time. Like anything else, he said agency approvals are also subject at times to political winds as well.

In addition to FERC approval, there are a slew of other agencies that measure the impact of a project, such as the Environmental Protection Agency and the Army Corps of Engineers. Add to that the list of state and local agencies that have their own review procedures, and it's easy to see why it’s an advantage for energy companies to build pipelines in the areas that will have the lowest impact on their surroundings.

Of course, the easiest option is to share an existing pipeline. Mark Pyatt, global lead of oil and gas operational integrity at international software company SAP, said joint venture agreements within the pipeline industry are commonplace. That way, multiple companies only have to negotiate once for easements and land acquisitions, although if a new company comes into the mix after the original approvals are granted — or if the owner of a dedicated pipeline want to sublet it to another firm — that company would have to secure its own approvals.

Sharing is also convenient, Pyatt, because it cuts down on multiple companies trying to justify the pipeline to residents who have concerns about safety or who might lose land to the project. "Change is always hard, and some people are against it," he said.

The pipeline contractors themselves are subject to state licensing laws, but there is no federal license necessary to perform pipeline work, only a federal project permit, according to Scott Berry, director of the Associated General Contractors of America’s utility infrastructure construction division. Because most pipelines are privately funded, they’re not often subject to the requirements of prevailing wages, minority contractor hiring or project labor agreements, he noted.

In fact, Trump’s American-only sourcing requirement for pipeline material is the first time that an agency has dictated to contractors how they should carry out pipeline construction beyond what the permit requires, according to Berry.

In addition, when those pipeline contracts are awarded, Berry said it’s up to the owner to decide how many contractors to use on the project, but on longer pipelines, it wouldn’t be out of the ordinary to see each segment bid separately.

The role of technology

Given the lengths of some pipelines, new technology has been a logistical boon for contractors, according to Pyatt. Software can ensure that materials are delivered on time and that current progress is keeping pace with the planned schedule.

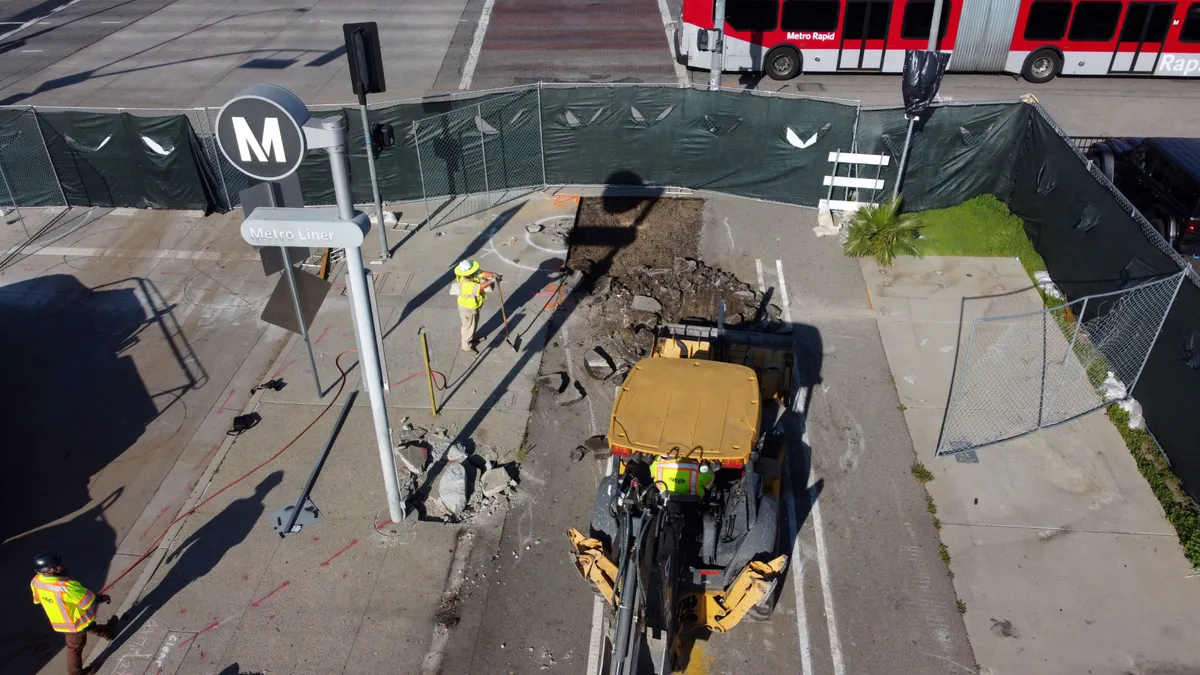

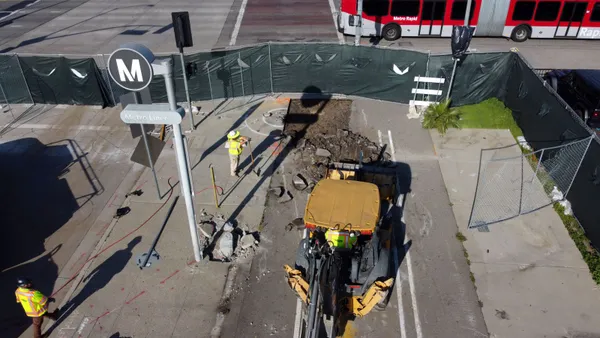

Drones, he said, can monitor construction as well with thermal and spectral imaging from start to finish. Of course, like any other construction project, a major challenge for contractors during pipeline construction is logistics. "It’s making sure people and materials show up to the job at the same time," Pyatt said.

Once construction is complete and maintenance crews take over, that's when technology becomes key, according to Pyatt. Most pipelines are required to use internal pipeline sensors for quick leak detection. Crews are typically on standby and are dispatched as soon as the data indicates a problem.

In addition, those same sensors can make sure that what goes in one end of the pipeline comes out the other. In some countries, it's not uncommon for unmanned sections of the pipeline to become targets for individuals who try to physically tap into the line to siphon off gas or oil for their own use, which can lead to an explosion along the line, according to Pyatt.

The biggest challenge for future pipeline construction

Berry said the most significant obstacle for pipeline contractors on the horizon is a usual suspect — a shortage of skilled labor. During the Great Recession, pipeline construction workers found jobs in the oil and gas industry, taking with them the specialized knowledge of equipment operators, pipefitters and welders. Some have returned to the construction industry, but many have not, and sooner or later, demand will outpace supply.

The AGC has contacted the Trump administration about the need to prioritize and fund career training starting at the high school level as part of his ambitious plans for infrastructure construction and continues to bang the drum about the importance of creating a worker pipeline for the future.

Berry said the ultimate solution will likely come down to a combination of approaches, whether it's trying to lure workers from other sectors or appealing to young people. The biggest challenge, however, will be to create a fundamental shift in the way people view a career in construction. "Nobody has a silver bullet," he said.