The construction industry faces a stark shortage of workers, but programs and people across the country are working at the local level to solve the problem. Help Wanted highlights grassroots efforts to recruit the next generation of construction pros.

Do you know of a group that is helping attract workers to the construction industry? Let us know.

It started with trying to win a healthcare project in 2016.

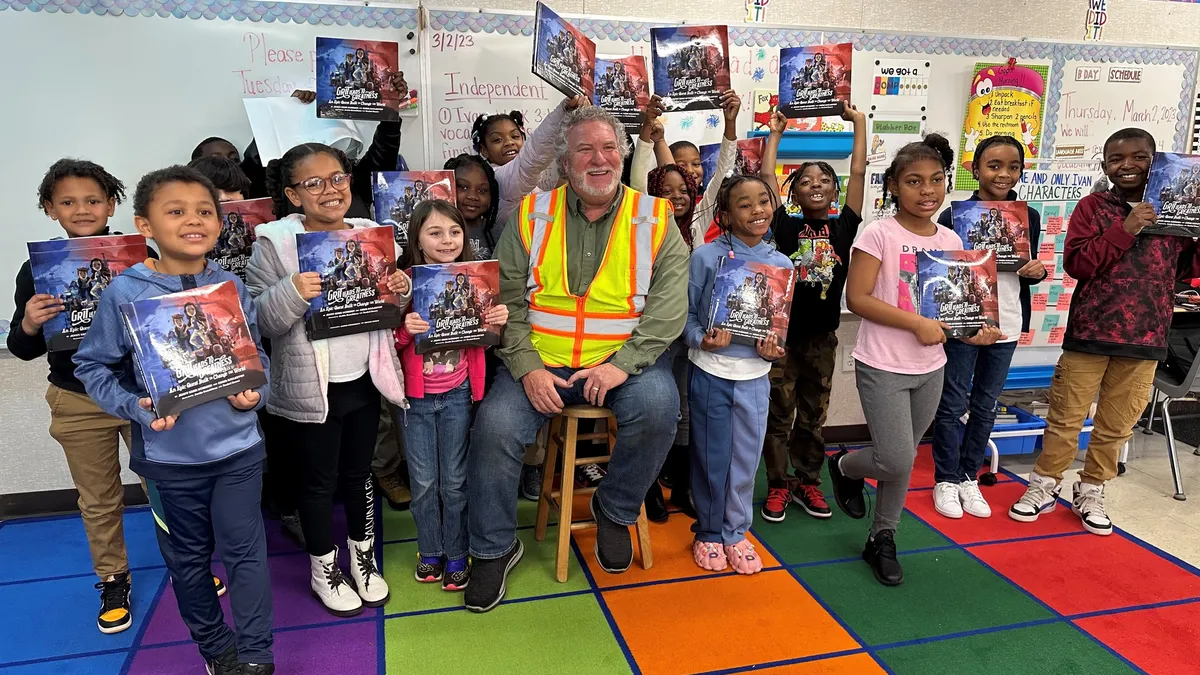

Messer wanted the Cincinnati Children’s Critical Care Building contract, and needed to set itself apart from other national firms. So Stan Williams, vice president of economic inclusion, helped create the Urban Workforce Development Initiative to train people from the neighborhoods near the hospital and place them in permanent jobs in construction.

The contractor pledged to fill 50 jobs with local workers by the project’s end, and said it achieved that goal with the aid of 16 different subcontractors and various social service groups.

In light of that success on the hospital build, Messer decided to continue a form of the UWDI program. The company pledged to add 45 jobs for locals across various urban projects by 2024, and Williams said 20 workers have already found their place.

Process and partnerships

The new workers are from majority-Black neighborhoods — a demographic that is under-represented in construction. Roughly 6% of construction workers are Black, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, though they make up over 12% of the general working population.

To find potential trainees in those neighborhoods, Messer partnered with social services nonprofit Easterseals, which owns Building Value, an architectural salvage outlet in Cincinnati. Williams said the partnership made sense, because they could use the deconstruction work to provide training to enter the building industry.

From there they found potential workers in the urban core of Cincinnati, and placed them in a 12-week program, earning $9.15 an hour. With each week, if workers showed a good attitude, arrived on time, wore the proper PPE and developed their soft skills, they’d get a green dot. After drug and background testing, Messer connected the worker with a subcontractor.

Getting the subcontractors on board was a matter of leveraging billions in backlog as incentive.

“We said, ‘We're gonna do all the work for you so that you don't have to do anything but take the person on. And we want you to try them out for three months. And if you like them, we want you to hire them,’” Williams said. Most jumped at the chance.

Things have evolved since that hospital project, which opened in 2021. UWDI participants now earn $10.15 an hour at Building Value and receive a $1,000 bonus upon finishing the 12 weeks, plus Messer revisits the subs at eight weeks instead of three months.

Removing barriers

Reginald Brock, an electrician with Archible Electric, says he got into the field through Building Value, which instilled in him the value of arriving early, working hard and delivering work on time. But even then, like many other potential construction workers, he faced obstacles. In Brock’s case, he didn’t have a car.

“Construction starts when the sun comes up, so buses are often not running that early,” Williams said. Even if workers in cities can rely on public transit, they sometimes have to catch multiple forms to get from A to B.

Since a lack of transport created a near-insurmountable obstacle for many potential workers, Williams and Messer partnered with another group: Wheels Cincinnati. The faith-based nonprofit provides a car for those in need for $1,500, after they detail to the organization how the vehicle will alter their life for the better.

Williams said Messer helps connect the workers with Wheels by ensuring they have a license and expunging any existing violations. From there, Messer pays for the car, using the worker's $1,000 bonus, which they forgo. Then, over the course of their first weeks at the sub, the worker pays back the additional $500 interest free.

Keysean Hartley, now employed by Valley Interior Systems, said he already had the self-discipline to work hard, but the program helped him get a car and develop the soft skills needed to land him his job.

“They helped me with getting a car, basically just getting my whole life together,” Hartley said. ”They played a huge part in my current success.”

Williams said Messer partnered with other groups to help bring attention to childcare, nutrition and budgeting programs, often important tools some of the targeted recruits don’t have.

No one-size-fits-all

Forty-five new workers by 2024 is hardly a drop in a bucket. Construction faces major demand to staff jobsites, and it’s no secret that large amounts of the workforce are retiring while others leave for other industries.

Nevertheless, Williams said it’s hard work to remove barriers, even for the people that Messer has reached most easily.

“I'm not sure I know how to scale this thing up to crank out a thousand people every year, because the issues and concerns that people have need to be addressed on an individual basis,” he said. “You just can't say, ‘Well, everybody's got a driving problem, so we're gonna solve the driving problem and they can go to work,’ or ‘Everybody has a childcare problem, we're gonna solve the childcare problem.’”

Still, Brock said as places like Building Value help their communities, that can show a path to success, especially to younger people. Brock said had he known about his options earlier, he would’ve tried to join a union as an electrician right out of high school.

Hartley said transportation, education and childcare can stand in workers’ way, but he felt they ultimately hold the keys to their own success. Programs like UWDI help show them the door to a long-term career.

“I plan on continuing down my path because I believe in myself and I believe in the people that helped me,” Hartley said.