When it comes to startup havens, Silicon Valley is top of mind. The offshoot of the San Francisco Bay Area is known worldwide for its massive cluster of tech firms worth billions of dollars.

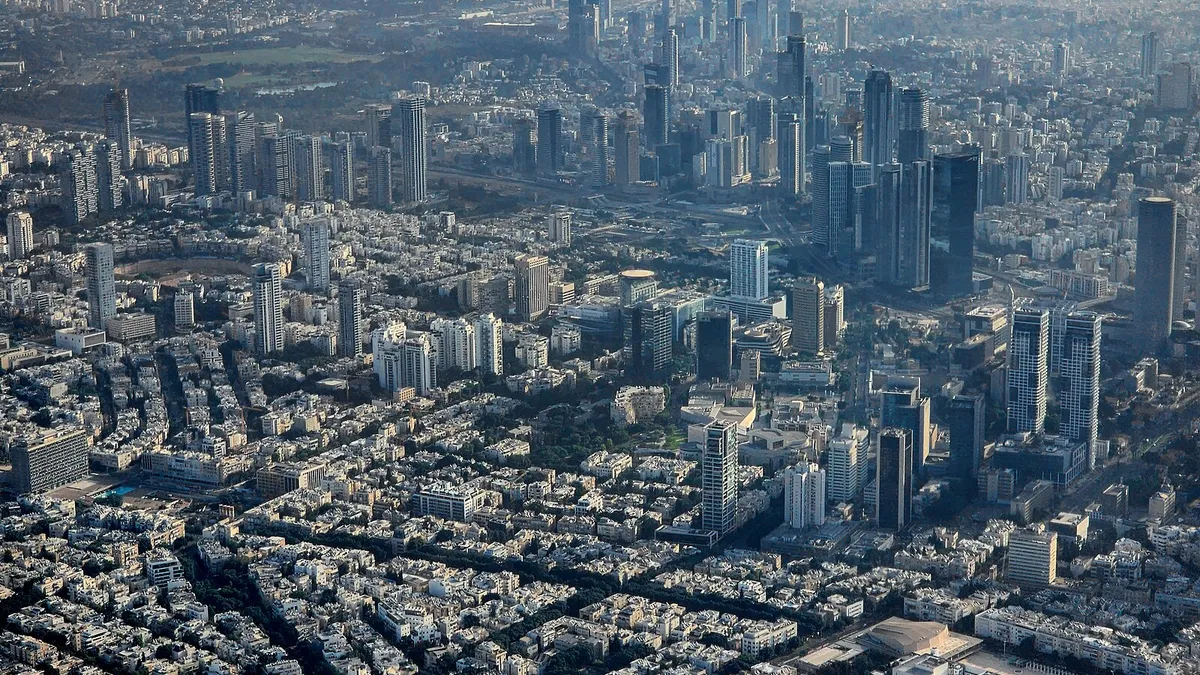

But, in the realm of construction innovation, there’s another area of the world where burgeoning technology firms can find support and funding: Israel.

The country is one of the most promising startup ecosystems in the world— it’s the third highest ranked country in the world for startup activity, behind only the United States and the United Kingdom, per Israeli research firm StartupBlink.

Budding entrepreneurs in Israel who seek to build their own businesses enjoy strong support systems, government funding and access to investors, who see the value the country brings in the startup scene. However, Israel’s strengths wane as these businesses seek to expand beyond the country’s borders, leaving them to go elsewhere to grow further.

Construction Dive spoke to several startup executives and experts, who all praised the country’s development ecosystem and attention that budding entrepreneurs receive. They also listed the unique challenges businesses face there.

Connectivity is key

Creating startups from scratch and building a business from nothing is in “the DNA of Israelis,” said Meirav Oren, the CEO and co-founder of construction technology firm Versatile, which started in Tel Aviv.

“It's such a fertile ground for an industry that needs great solutions and great companies to be created,” said Oren, who is also the chair of the Tel Aviv chapter of the Society for Construction Solutions, an organization focused on the future of the industry.

Aviv Leibovici, co-founder and chief product officer of Tel Aviv-based construction software firm Buildots, credited the Israeli military for its role in giving business people the skills they need to succeed in a startup environment.

Many Israelis — barring exceptions based on race, religion or health — are required by law to serve in the country’s military: Men are required to serve for 32 months, while women are required to serve for 24 months. Among the most famous of these programs is Unit 8200, an elite cybersecurity section within the Israeli Defense Force that Forbes called “Israel’s secret startup machine.”

For Leibovici, making connections within the construction industry was a large, but surmountable, task. He believes it was easier to accomplish in Israel, as opposed to Britain, where Leibovici is currently based, away from the Tel Aviv headquarters where Buildots was founded in 2018.

“Israel is such a closed, small sort of community in many ways that you may easily get to, to explore,” Leibovici said. “People tell you, ‘Oh, you're trying to start a tech company in this space? That’s fantastic, that’s amazing, come in.’”

Leibovici said that because of those connections, he was able to get a strong understanding of the market very quickly, through meetings with CEOs and days on site with project teams, finding the ins and outs of the industry.

Cheli Wasserman, the CEO of Bimmatch, a construction software firm based in Tel Aviv, echoed Leibovici’s sentiments.

“Israel enjoys a thriving startup ecosystem support, with a high concentration of tech companies and a culture of innovation that provides valuable and supportive networking opportunities for legal, business and development inquiries,” Wasserman said.

It’s all about the money

Those doing business in Israel say they reap benefits from the role of the government in creating opportunity and the involvement of others within the tech arena that supports entrepreneurs.

“Someone knows someone all the time, and they're able to give you that intro a lot of the time more than you're going to find in other places,” said Molly Livingstone, the chief of connections and ecosystem manager for MassChallenge Israel, an offshoot of Boston-based American startup accelerator MassChallenge.

Livingstone pointed to specific programs the government of Israel has engineered to grow startups, such as the Israel Innovation Authority. The IIA, by acting alone or partnering with other countries such as Japan, the U.S. and India, as seen on its request for proposals page, can provide funding and support for Israel-based companies looking to break into the fields of their choice.

The IIA has an annual budget of roughly $500 million, according to Hagit Sela-Lidor, the IIA’s head of international marketing. After what Sela-Lidor called a rigorous screening process, startups can receive a large percentage of the funding they ask for. According to the agency’s 2023 annual report on the state of high-tech in Israel, the agency spent around 1.7 billion Israeli shekels, or around $449 million, in direct funding across its plethora of grant programs for startups and businesses.

However, the government won’t solve all funding woes.

“If you're asking for $100,000, you will never get the full amount of the money. You’ll get, at the maximum, up to 85%. And the rest has to come from private funding. In that way, we engage the private sector to jump on the ship with us,” Sela-Lidor said.

Despite government aid, this figure pales in comparison to the private sector, which is a large part of the equation — in just the first six months of 2023, the Times of Israel reported that startups raised $3.9 billion from private financing rounds. This large figure is also a 29% drop from the second half of 2022, per the Times.

Networking sometimes occurs even before a business is founded. Sources pointed to the Israel Institute of Technology, or the Technion, a university with a reputation rivaling the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, as a large foundation for entrepreneurs.

“Israel is a very active ecosystem,” said Gonzalo Galindo, the president of Cemex Ventures, the venture capital arm of Mexican contractor Cemex. “We have traditionally seen quite a few companies from Israel in our startup competition that we run every year.”

“I think they really pull money within the boundaries of what they can do and the size of what they can achieve,” Galindo said.

Room to grow?

Despite all that the country has going for it, Israel has its own share of issues for startups, and for those in the contech space, the local construction industry isn’t pushing boundaries, according to Rafael Sacks, a professor at Technion in civil and environmental engineering.

“There are very few of the companies that actually run major experiments of any kind here with the local industry that have brought them ahead,” he said.

Sacks said any businesses that want to grow must do so abroad, and many leave Israel for more opportunities in the U.S. and U.K. In addition, rising tensions as a result of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s judicial overhaul has led some startups across all industries to consider incorporating in the U.S., according to Reuters, and created an air of uncertainty in the sector.

“The market share is very small, not very sophisticated in construction, and not willing to take risks. I could count on one hand the number of general contractors who are willing to engage with these companies and use their products,” Sacks continued. “It's easy to start up. It's not easy to make money.”

Additionally, firms that have operations outside of the country have reported issues receiving their funding from the IIA.

For instance, if a company's research and development team is located outside of the country, it could present an obstacle for getting funding from the IIA, one source, who requested anonymity out of fear of jeopardizing a funding application, told Construction Dive.

Inbar Blum, the head of the growth division at the IIA, said that while she understood companies wanted to grow and branch out, it was important to the IIA that the ideas and tech remained Israeli.

“We have very good talent here in Israel. We want to use it for good reasons — to change the world, to cope with all the challenges and have solutions for the challenges in the world through Israel,” Blum told Construction Dive.

Hagit Sela-Lidor, the IIA’s head of international marketing, said it was also rooted in service to one constituent group — taxpayers. Sela-Lidor added that companies were free to pursue overseas and foreign expansion, but they would have to pay a fine, which Sela-Lidor said startups know about in advance.

“Our interest is, of course, to finance companies that hold their IP locally,” Sela-Lidor said.

Through the spirit of innovation, many who enter contech do so as a result of a pivot, and not as their first choice. Sacks said that many who enter the field of construction look at other fields that their peers are entering, such as cybersecurity, biotech and others, and see that construction is “greenfield.”

“They find that the field is very crowded. Inside the medicines and biotech unit, and then they suddenly look at construction,” Sacks said.