Getting people from point A to point B as quickly and efficiently as possible is the basic goal of mass transit, and, generally speaking, faster is better. Much of the world, however, is far outpacing the United States in high-speed rail adoption.

In fact, according to a 2012 Congressional Research Service report on the status of high-speed rail in the U.S., there is only one rail line and one service that could be considered high-speed, Amtrak's Acela train serving the Northeast Corridor from Washington to Boston. Although Acela trains, which carry approximately 3 million passengers per year, have the capability to reach speeds of 165 mph, they are typically authorized to operate for a few minutes on certain segments of their routes only up to speeds of 150 mph. That pales in comparison to, for example, China's nationwide high-speed train network, which boasts a ridership of nearly 1 billion per year and features trains that can travel as fast as 300 mph.

But some states in the the U.S. are trying. Although Florida, Ohio and Wisconsin each turned down federal funds to help build high-speed train service, California took up the banner and is currently underway with construction of a "bullet train," which the California High Speed Rail Authority hopes will be the nation's first true high-speed rail line. Nevertheless, although general enthusiasm for the project seems high, it has not been without its problems.

An October 2015 Los Angeles Times investigation suggested that authority officials had not been completely honest about the costs or the logistics of the project during the initial funding phase. The Times article led to a flurry of special legislative sessions and investigations, which, so far, have not yielded a "smoking gun" indicating any intentional deception on the part of rail officials. However, the system has been plagued by delays, cost overruns and segment changes that indicate a long road to completion.

So why is the U.S. so far behind in what seems like an increasingly common service for the rest of the world?

Regulatory hurdles

President Barack Obama had high hopes for a U.S. high-speed rail program, but much of those earmarked funds went toward upgrading existing Amtrak service rather than going into high-speed specific projects, according to a New York Times report. And aside from the big bump in funding made available as part of the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, high-speed rail receives only approximately $1.5 billion a year in federal money, according to Richard Harnish, executive director of the Midwest High-Speed Rail Association, an advocacy group based in Chicago.

Regulations are also a barrier to high-speed rail's wider implementation. For starters, Harnish said the country's Buy America laws — remnants of the $50 billion General Motors Great Recession bailout — are preventing high-speed rail cars from being imported into the country, as there are currently no manufacturers producing them in the U.S.

"There isn't a single high-speed rail factory in the United States today, and there is no supply industry to supply those factories, even if one were to get built," Harnish said. This requirement derailed a planned China-backed high-speed system between Las Vegas and Los Angeles just last month.

But even if the Buy America rules were not in place, cars made in other countries don't meet American safety standards as set by the Federal Railroad Administration. Rail cars made in the U.S., Harnish said, are designed to protect automobile passengers in case of a crash rather than the rail passengers, the opposite of the way cars are designed in many other countries.

"Our regulations create a train that is really heavy, so it's much more likely to get into an accident," he said, "and it protects the vehicle more than it protects the people inside the train, whereas the rest of the world's focus is on keeping the train solid and absorbing the forces of the crash in order to protect the people inside the train." The Federal Railroad Administration is working to change those rules, but the agency needs "a little oomph" in the progress department, he said.

Eminent domain and land acquisition obstacles

There are also the issues of eminent domain, according to attorney Anthony Leones with Miller Starr Regalia in California. High-speed rail projects like the California bullet train, he said, can get a bit sticky because they're dealing with a project that requires businesses and families to be relocated. "Property owners, and often businesses that even just lease space, are compensated for their land or for damages, such as in the case of a farmer whose field has been cut in half by newly laid tracks," Leones said. However, damages to the business are separate from the land damages and fall into a separate category of "goodwill damages," he added.

"These can be difficult issues to deal with and perhaps could be causes for delays," Leones said. California has a process that agencies like the CHSRA have to follow before they can seize property, and this can also result in a rocky schedule start. The project, he said, has to be "clarified and defined" in order for the seizure process to begin, as the state wants to be absolutely sure that the taking of a particular property is necessary to complete the project. So if there are any loose ends or holes in the project plans, they could delay land acquisition.

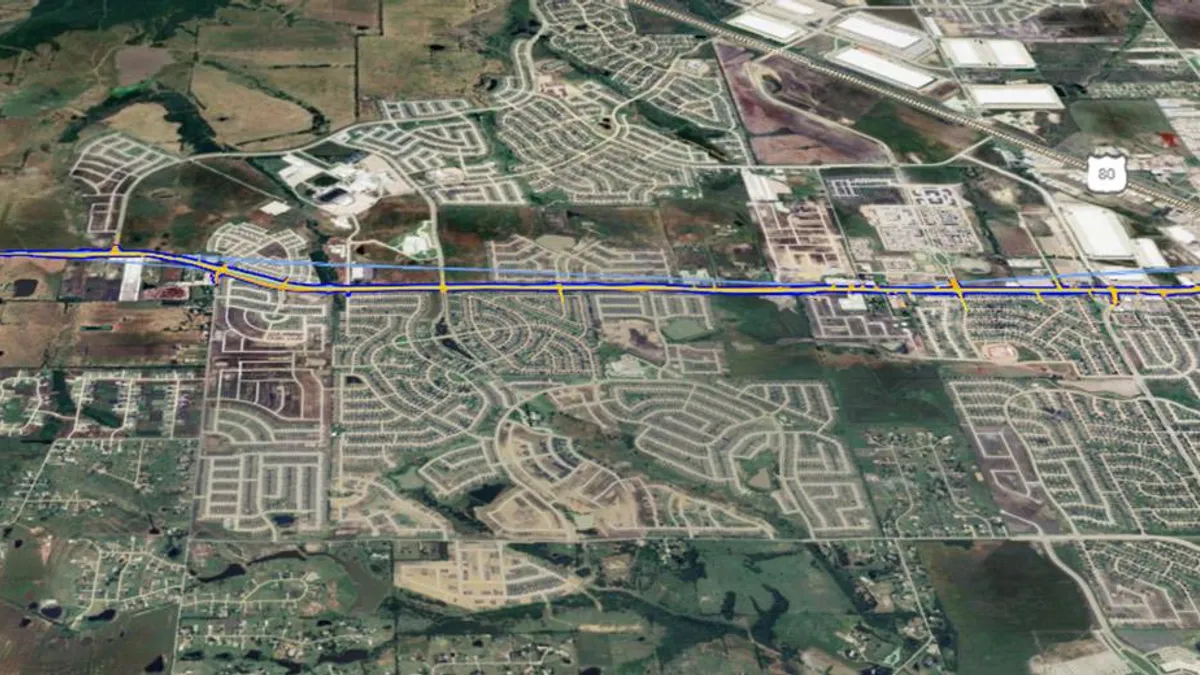

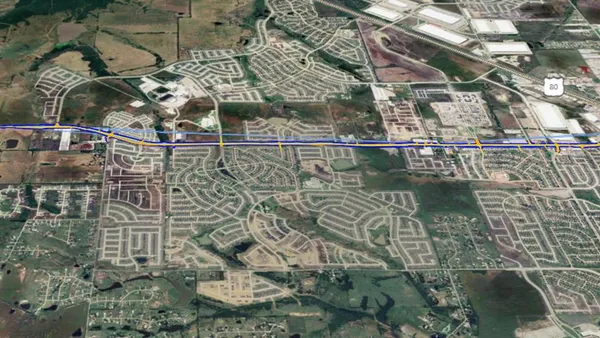

While it is unknown if this is one of the reasons that the CHRSA has experienced land acquisition delays, the rail authority's inability to secure enough property for contractor Tutor Perini to begin work in 2013 resulted in nearly $64 million in change orders to pay for the mobilization and remobilization of equipment.

Is demand too low?

Some point to Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration demand models as another factor preventing expanded high-speed rail in the U.S. Harnish said these are often "rigged" in favor of highways versus mass transit. The demand models assume "a very steep growth curve for future driving," he said. Harnish said increased urbanization means that the likelihood of such a projected increase in driving is unlikely. Demand models, he said, also assume that there will always be "cheap oil in Texas," so there can always be "cheap driving."

On the transit side, Harnish said the models assume that there won't be money to put into high-speed rail and that ridership won't increase that much. In addition, he said the FTA ridership models are all based on people going to work in the morning, yet that segment of riders is a very small percentage of trips.

And then there is the fact that Americans love their automobiles, and the constant lure of the open road is engrained in the country's psyche. Leones said he believes that "public transportation in general is not a part of our everyday life and everyday culture like it is in Europe and other places." In addition, Leones said, America's roads and highway systems are better than elsewhere in the world.

Harnish disagreed with that assertion. "So you think that a French person doesn't like that autonomy, or a Spanish person doesn't like being able to just get in a car and go whenever they want to go?" he asked. "Are we that completely different than everybody else in the world?"

He said that of course it's easier to "get in your car," but, after a while, people begin to appreciate the comfort and convenience of mass transit. "Everywhere we build transit or make biking safe or make walking safe, people walk, and they take the train, and they take the bus," he said. He added that this only happens when mass transit service works, so people in the U.S. don't have as much of a choice.

How can rail advocates turn the corner, then, and get states, federal agencies and private investors on board with high-speed rail? Harnish said the successful completion of at least one project is critical to the future of high-speed rail in the U.S. "That's why California is so important," he said. "Get that thing running trains."