The average North American construction dispute, according to the most recent report from design and consultancy firm Arcadis, took about 14 months to resolve in 2016 — the longest of anywhere in the world — and had an average value of $21 million. In its report, Arcadis also revealed that two of the most common reasons that contractors end up battling it out in the courtroom or in some other form of dispute resolution were errors and omissions and unsubstantiated claims.

This is where BIM comes in.

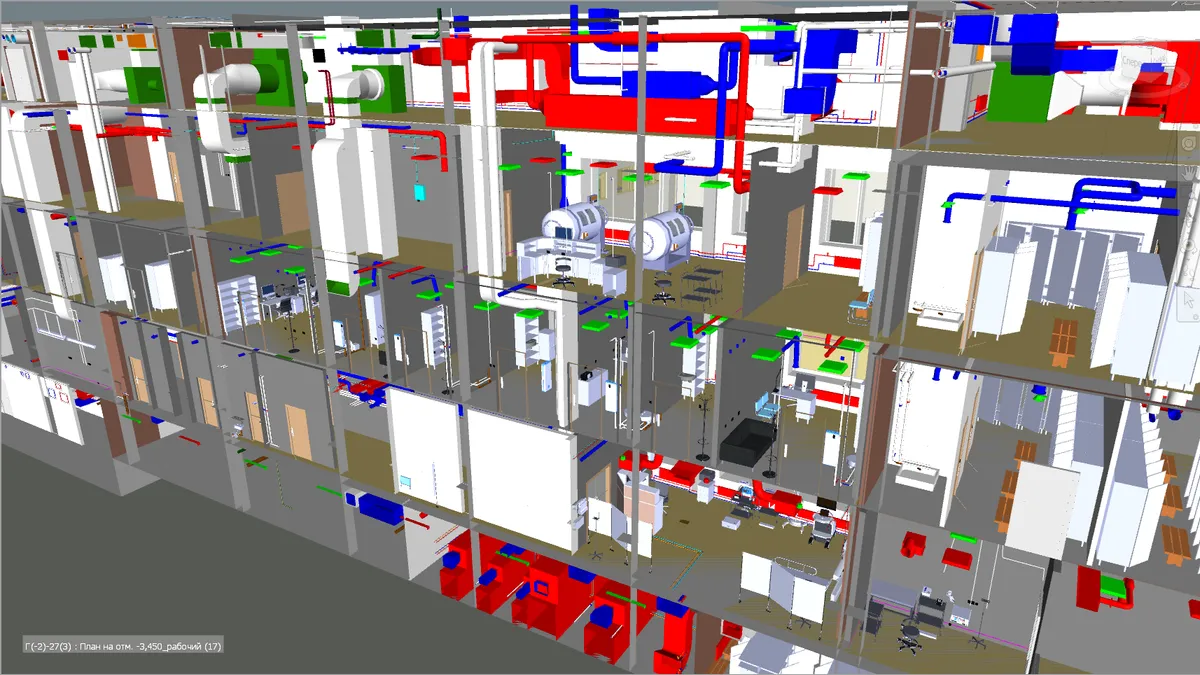

Many contractors are familiar with BIM from working with it themselves, seeing other construction companies or designers on the same project use it or from reading about it in an industry publication. Simply put, BIM allows contractors, architects, owners and other stakeholders to generate and manage 3D versions of a project through its entire lifecycle — from the conceptual phase to operations and maintenance.

Owners in particular look to BIM to reduce construction costs and aid in post-construction asset management programs. For example, the Los Angeles Unified School District said BIM saved the district $12 million in construction costs and is helping coordinate workflows and facility management for its $9.5 billion capital program.

Cost savings is one of the reasons that the United Kingdom mandated that contractors engaged in government work start using a basic level of BIM. Some U.S. government agencies require their contractors to use the 3D modeling system, but a national standard has not yet materialized.

Referencing BIM in the dispute process

BIM can be invaluable during a dispute process when contractors and their attorneys must take a forensic look back at the project to verify that the scope of work completed matches what the contract required or to either defend against or pursue a claim of defects or omissions.

As long as those using BIM are diligent about maintaining the model so that it represents the most recent, accurate information about a job’s progress, it’s a no-brainer that it would be used as a go-to reference when there is a disagreement that relates back to some physical aspect of the work.

However, if BIM is potentially still working its way to first-time users in the construction industry, how often do litigators have an opportunity to use it in their work? “In terms of dispute resolution,” said attorney Quinn Murphy of Sandberg Phoenix in St. Louis, "it's really new.” However, BIM is being used in mediation and arbitration, he added, to demonstrate things like the impact of changes during the course of projects.

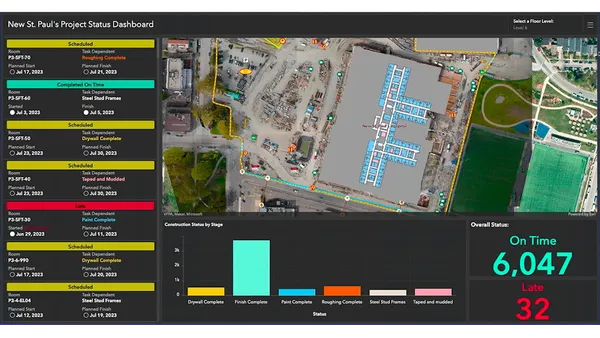

For example, if a general contractor makes a claim against one of its subcontractors alleging that the late arrival of material created a domino effect and delayed other trades, the parties can go back into the BIM model and run different date-based scenarios to determine what the impact truly was. This can help determine the true cost of the delay in time and money or aid in dismissing the claim altogether.

The impact of design changes, such as using a material not specified in project documents, can also be evaluated in variations to the existing BIM model.

And it makes sense, Murphy said, that BIM is typically only used in a legal proceeding part of the project in question — not after-the-fact modeling.

A record of project progress

BIM can also be used to document work at specific points in the schedule. One way to create such a record, said Sam Arabia, director of engineering and BIM services at New Jersey-based construction management and general construction company Torcon, is through laser scanning. This technology, which uses targets and a laser scanner to capture the physical characteristics and dimensions of a space, can then be displayed using BIM.

The images created from a laser scanning session, he said, could also be helpful in determining fire or accident damages for insurance claim purposes.

“How do you document the damage? You can overlay a scan into the BIM model,” Arabia said. The layered visuals can show how the event affected the project and where repair work is most needed, he said.

Because BIM provides a record of exactly how a project was built and a timeline of who authorized changes and other actions, it could reduce frivolous claims or those borne out of frustration, Murphy said. The record is the record.

But the most significant role BIM plays in dispute resolution, Murphy said, is helping the parties to a construction contract avoid them. One of the things BIM does, Arabia said, is add complete transparency to a project. All the participants know what they’re getting into. Plus, owners and other stakeholders who are not on the job every day have a virtual means of participating in the building process, he said.

And for contractors and the design team, BIM is a way to iron out potential conflicts, clashes and design errors before a shovel hits the dirt, allowing all parties concerned to minimize the chances of ending up in court or some other dispute resolution arena.

Protecting your assets

As the technology behind BIM improves, said Sarah Hodges, director of Autodesk's construction business line, it will provide an even greater opportunity for claim avoidance through enhanced collaboration. She described the future of BIM as an ecosystem, connecting hardware and software through tools like the cloud-based project management software platform BIM 360, where contractors can deposit, maintain and work with project information in one place.

The platform also provides a one-stop source for attorneys or others investigating a claim to get the most complete picture of a project’s lifecycle, its past and the actions of decision-makers. "That’s when forensic BIM becomes a powerful tool,” she said.

Nevertheless, contractors who want to use BIM in dispute resolution down the road must make sure that the results of laser scanning, BIM and the like are incorporated into the official project contract documents, Murphy said.

In addition, Arabia cautioned that BIM-related tools have limitations. If the intent is to decide why something didn’t work, a tool like laser scanning, which provides a snapshot of conditions at a certain point in time, won’t be much help on its own. Participants must look at all aspects of a project holistically to get a complete overview. “You can’t do it in a vacuum,” he said.