As a variety of forces put pressure on water infrastructure, Ian Dickinson sees the industry growing and adapting to meet these new challenges.

After more than three decades in the sector — most recently as executive vice president of infrastructure at Calgary, Canada-based Graham — Dickinson joined Broomfield, Colorado-headquartered Flatiron in January to lead its growth in the water and wastewater infrastructure sector.

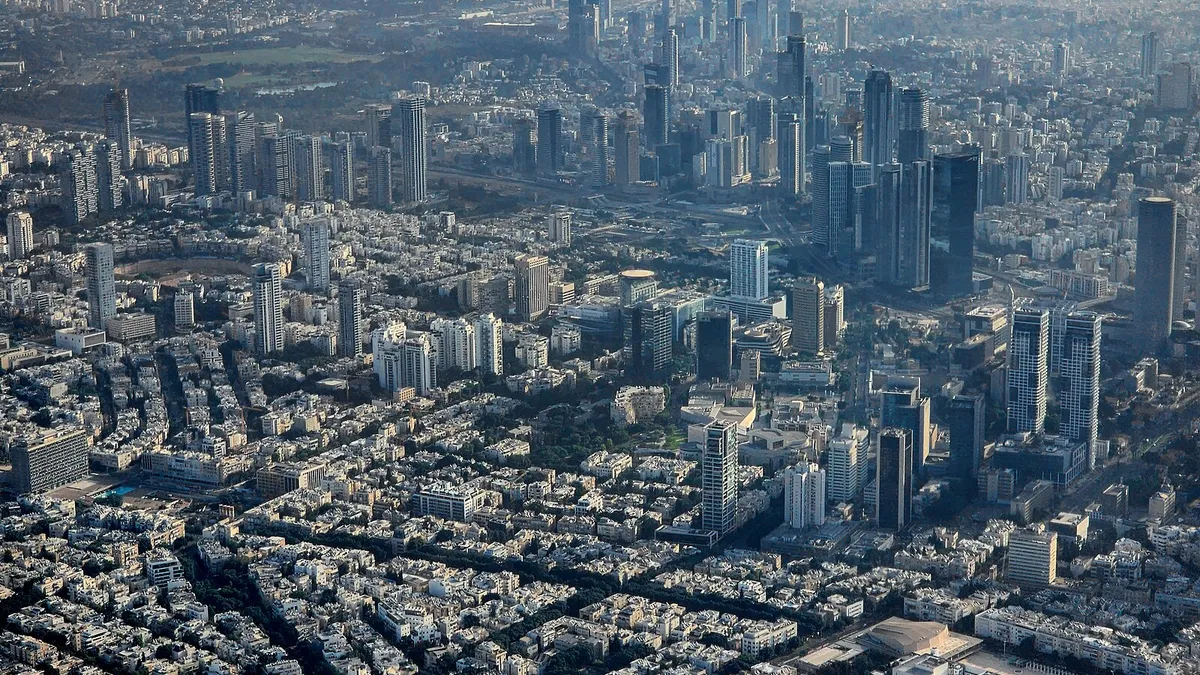

Demand for these types of projects hinges on population growth and urbanization, environmental degradation, aging infrastructure and higher safety standards, after the EPA in April designated two types of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances — also known as PFAS or “forever chemicals” — as hazardous.

“Many plants which were upgraded in order to meet tertiary standards over the last 20 years are now going to have to be upgraded again in order to remove these forever chemicals and other compounds which we know are now a cause of public health concerns,” Dickinson said.

Here, Dickinson talks with Construction Dive about what’s driving the water infrastructure boom, how the industry is evolving and tips to manage supply chain challenges.

The following has been edited for brevity and clarity.

CONSTRUCTION DIVE: Why is there such a boom in water infrastructure projects right now?

IAN DICKINSON: I think it’s climate change, I think it's population shift, either when there’s urbanization or inward migration. Public health data that's available today now tells us that things like PFAS are a concern, and there are just ever-increasing standards which are designed to protect people and the environment.

The water stressed areas are typically in the South and the Southwest, really from California and across to Texas. In Florida, it's a bigger problem than you might think, and even on the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains, there are areas that are very water stressed because not a lot of moisture gets across the mountain.

What types of water projects are you commonly seeing?

Wastewater treatment is a $60 billion to $100 billion a year market, and there are dozens, if not hundreds, of communities across North America that need to build new infrastructure to address their combined sewer overflows.

There are some very interesting projects happening in California that we're involved in to take wastewater treated to very high standards and use it to recharge aquifers or reservoirs, and then it's extracted for drinking. These types of projects involve big pumping stations, pipelines, tunnels, reservoirs and new treatment plants.

I think when the idea of taking wastewater and treating it to a very high standard and then reusing it for drinking water was first floated, people thought it was a terrible idea and they thought that was something to be avoided at all cost, but now most places in Southern California are completely accepting that it's absolutely unavoidable.

Another type of project is flood defense. We have a project right now in Virginia Beach to enhance the city's flood defenses, which will protect the city in those instances where they have high rainfall at the same time as a high tide. It's a type of project that we know there will be a lot more of because a lot of municipalities are in similar situations.

How is the water and wastewater construction industry evolving?

One of the things that has really changed in the time I've been doing this has been the standard that we work to in terms of the drinking water standard, the wastewater effluent discharge standards. When I started my career 33 years ago, most larger treatment plants would have primary and secondary treatment, although there were still some cities in coastal locations that didn't have secondary treatment or even primary treatment. Now it's very common.

The complexity of the treatment technology that we're installing, particularly for tertiary treatment, has increased significantly for things like ozone systems, oxidation, membrane systems, filter systems and so on. The same is true on the drinking water side.

When I started my career, there were still some fairly large communities that didn't have filtration. One project I'm proudest of is when I built the wastewater treatment plant in Victoria, British Columbia. That was a really unusual situation because that was actually one of these cities that had no wastewater treatment until December 2020.

What are some of the biggest challenges you’re encountering?

Water projects are quite vulnerable to supply chain challenges, because almost every project will have things like transformers and a big electrical switch gear, and those are some of the things that have been really significantly affected.

Specialist process equipment is typically patented and trademarked, so you can't go down the street and get it from somebody else. You're often locked in, to possibly as few as one, sometimes maybe two or three, but certainly only a small number of vendors. And it drives the critical path in projects.

We have to get that key process equipment and the main electrical equipment on order right at the beginning of the project to receive it in time to complete the job. We’ve seen projects which would have taken two or three years extend out to three or four, simply because of the longer lead times.

How can contractors be successful in building these types of projects?

With the volume of work that we have, we're able to leverage some of our relationships. But really, you just have to get out in front of it more than anything. We might be able to trim a little bit of time off, but fundamentally, the mitigation is to get this stuff on order right away at the beginning of a project.

With a progressive design-build model or a construction manager at risk-type contract, we can say to the owner, “Look, if you’re willing to do an advanced procurement package six months before, then we can take six months off the construction period.” So we're very often doing that. We find that a collaborative contract model is a really excellent way to mitigate this risk.