Project labor agreements (PLAs) are a frequent point of contention in the construction industry, particularly when private contractors are forced to sign these typically union-negotiated deals. The pushback is strong enough that stakeholders are doing what they can to get government-mandated PLAs banned at both the state and federal level.

In the simplest terms, a PLA is a collective bargaining agreement between an owner and one or more trade unions based where the project is located. These pacts determine how much contractors will pay their workers, what benefits they will provide, how many breaks employees get each day and how labor disputes will be resolved.

In other words, the deals govern just about anything related to how both union and nonunion workers are hired and treated on the job. In return, unions typically agree to forego protest actions like strikes and promise to provide enough manpower — at a predictable cost — to keep the project on schedule.

Those on both sides of the issue point to studies that come down in their favor, showing that PLAs either save projects money or cost them more.

Contractors are most likely to encounter PLAs on publicly funded projects. But in union strongholds like New York City and Los Angeles, it’s not uncommon for owners of large private projects to use them as well.

For instance, the Los Angeles Stadium and Entertainment District at Hollywood Park, owner of the new $4 billion Los Angeles Rams stadium complex, entered into a PLA with the local trades, even though the project is privately financed.

And after a contentious public squabble and dueling lawsuits, New York City-based developer Related Cos. and the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York (BCTC) finally reached a deal on a PLA for the second phase of the $25 billion Hudson Yards project in Manhattan.

PLA advocates say that these project owners want to reap the benefits of a reliable, well-trained and fairly paid workforce, and that could be true, said Ben Brubeck, the Associated Builders and Contractors' vice president of regulatory, labor and state affairs. “On some private PLAs,” he said, “there has been language that is not offensive or discriminatory. It’s really up to the owner. There’s actually a cohesive win-win approach in some instances.”

But sometimes the owner’s decision to go with a PLA is a result of intimidation and bullying, Brubeck said. For example, in California, he said, lawyers representing unions will threaten the use of the state’s toughest environmental law — the California Environmental Quality Act — which allows third-party interveners to file legal actions against projects on a wide variety of grounds and potentially stall them for months, even years. This tactic is what Brubeck refers to as “greenmail,” or environmental blackmail.

“That's why you see a lot of these private developers end up throwing their hands in the air and saying, ‘We'll sign a PLA. This is going to be good,’ and then kind of grit their teeth and go forward with it,” he said. “They know they're going to pay more and they know they're getting had, but at the same time, they need to get the project moving forward."

And all the benefits that supporters of PLAs claim they offer, Brubeck said, can be achieved through standard construction contracts anyway. Construction companies can be required to adhere to local hiring requirements, a safe workplace, apprenticeship programs and more.

Concerns over wages, union requirements

These are not the provisions that groups like the ABC object to, however. When industry associations are up in arms, it's usually over the purported increased costs of paying prevailing wages and fringe benefits, or the requirement that employees go through union-sponsored training, or mandates that employers hire through the local union hall or even that a nonunion contractor’s employees join a union.

“We don’t see a project labor agreement as anything but a partnership,” said Dan Langford, executive secretary-treasurer of the Southwest Regional Council of Carpenters, which represents more than 50,000 union members in Southern California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, New Mexico and Colorado.

This partnership view, he said, applies to both private and public projects. “We give them a great product. We do [the work] on time at the budget or under budget,” he said. “We give a career path to people that live in the communities where those projects are done.

“We know that our members are going to make a good, middle-class wage, [enjoy] a great medical plan and then a pension plan for when they are too old to do this really physically demanding work. [PLAs] fund apprenticeship programs that train the future of our industry. We see it as good for both sides — the developer, the awarding agency and for us, the union.”

Anti-PLA arguments, according to Gary LaBarbera, BCTC president, are simply false narratives designed to demonize unions and take attention away from the real reasons that groups like the ABC oppose PLAs.

“It's not about inclusion or lack of competitiveness," he said. "It's about trying to keep wages and benefits suppressed. It's about being able to have control over workers so that they can be manipulated and exploited … and that is why there's opposition to project labor agreements.”

PLAs establish standards, he said, that help root out bad actors like labor brokers, who typically use threats of deportation or even violence to keep immigrants working at substandard wages with no benefits and no safety training.

And both Langford and LaBarbera don’t discount the possibility that nonunion contractors might want to stay away from PLAs in order to keep their workers from being exposed to construction jobs — just like theirs — that pay a higher wage and comes with more benefits.

"If you take a worker that maybe has been paid cash,” Langford said, “or maybe has been paid under what we call the area standards, has never had any benefits, and then they go to a project labor agreement and they work equally as hard, and all of a sudden they're making a little more money, maybe for the first time, they have benefits that cover them and their family. There’s a possibility that … a worker might take advantage of that and want to [do] union work for the rest of their career.”

PLAs, LaBarbera said, are designed to create local jobs and, through good wages and benefits, stimulate the local economy.

Regardless of the benefits that PLAs can provide workers, however, the private construction industry still sees them, under many circumstances, as barriers to open-shop competition and have been busy lobbying lawmakers at the state and federal levels to do away with their mandatory use. Currently, 25 states, primarily in areas of the country with a strong nonunion construction industry, now prohibit government-mandated PLAs, with Kentucky the latest to join their ranks.

While the Associated General Contractors of America neither supports nor opposes the use of voluntary PLAs — some local chapters even help negotiate them on behalf of their members — it joins the ABC in opposing government-mandated agreements.

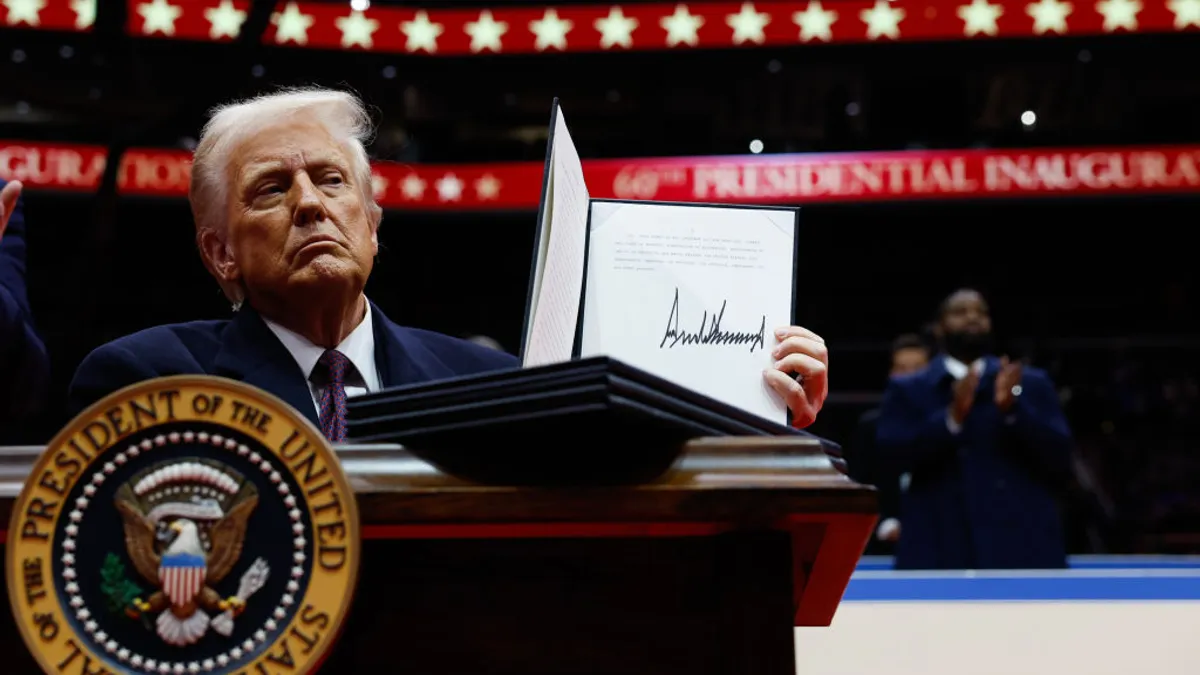

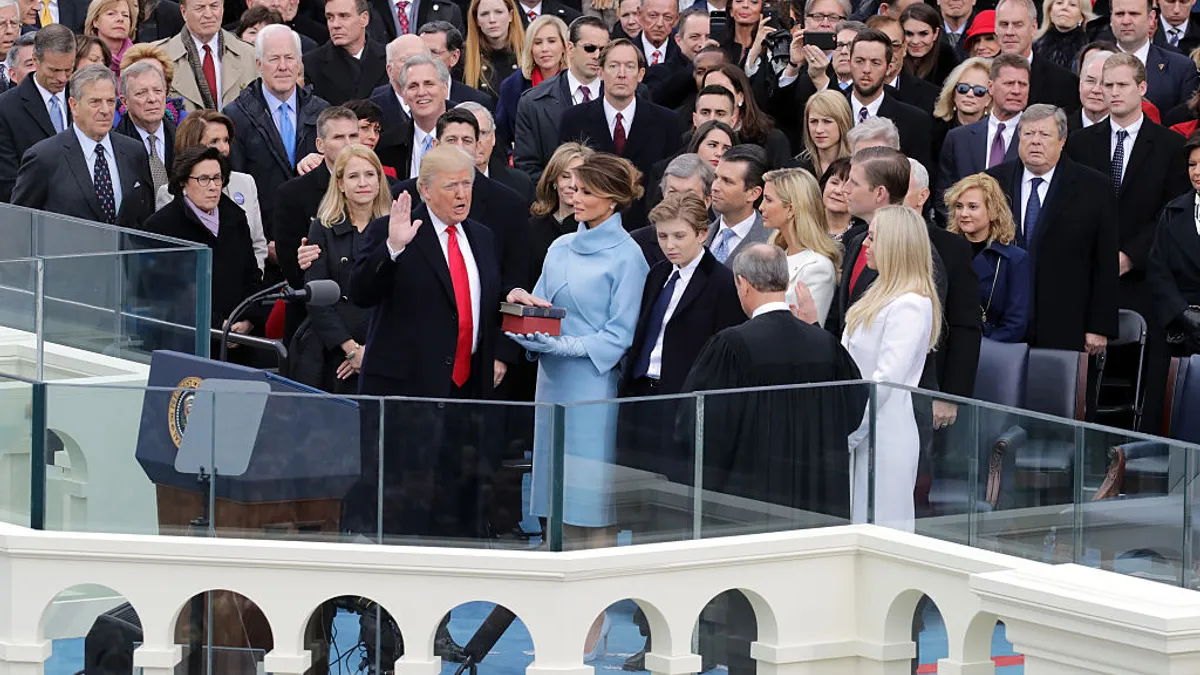

Both organizations are asking the current administration to rescind a President Barack Obama-era executive order that encourages federal agencies to use PLAs for construction projects worth $25 million or more.

Jordan Howard, director of the AGC's federal and heavy construction division, said the otherwise construction industry-friendly President Donald Trump has not indicated he will make a move on this issue.

“Things may not get headlines, but, on the regulatory front, he’s been very helpful," he said. "[However,] there’s been silence on this issue." This is the best chance to change the law given the Democratic House, he added. “We remain hopeful,” he said, “and we’re going to keep pushing on it.”

But no one should expect the two sides to agree on PLAs anytime soon, and union advocates like LaBarbera are going to keep pushing as well.

“We're trying to give workers a path into the middle class. It is a fight. It's a fight every day,” LaBarbera said. “We have to fight not only to maintain our own standards, but we also have to fight to try and help other human beings regardless of race, gender and religion into an industry where they actually see a career path.”