The construction industry faces a stark shortage of workers, but programs and people across the country are working at the local level to solve the problem. This series will highlight the grassroots efforts that are helping to recruit the next generation of construction pros.

Do you know of a group that is helping to attract workers to the construction industry? Let us know.

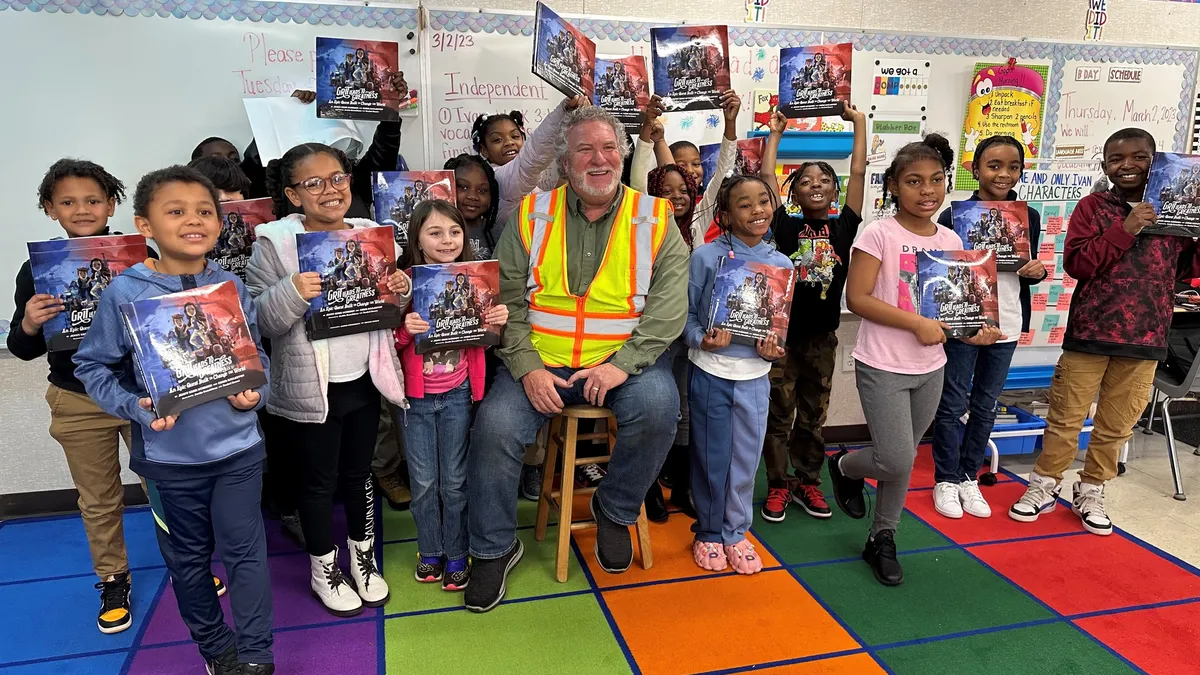

If you’re driving in northern Colorado behind a truck filled with scrap lumber, the person in front of you may be Robb Sommerfeld, and there’s a good bet he’s on his way to a classroom.

Co-founder of the National Center for Craftsmanship, Sommerfeld has worn many hard hats since the Fort Collins, Colorado-based nonprofit’s founding in 2006. The former Berthoud High School industrial technology and pre-engineering teacher recently transitioned into his role as executive director for NCC, an educational organization dedicated to the preservation, enhancement and sustainability of quality craftsmanship. Often partnering with members of the industry and local government, the group provides education and training to help retain and boost craft skills, including construction.

Fort Collins, Colorado-based NCC has offered multiple educational programs such as OSHA and machine training for women in prison and educational workshops on the deconstruction of buildings, which produces recycled materials instead of waste.

Scarcity, dumpster diving and scrap delivery

Josh Weissman is a shop teacher at Poudre High School in Fort Collins. His students have taken part in the deconstruction program, which he lauded as an invaluable, hands-on teaching experience.

Even before the pandemic and supply chain issues, craft-related classrooms like Sommerfeld’s and Weissman’s struggled to afford wood. They already had to “beg, borrow and dumpster dive” literally, Weissman said, with the ever-shrinking funds allocated to shop classes. The pandemic only increased material costs as supply struggled to meet demand.

“You're continually gauging your budget of material,” Weissman said. “This guy wants to build a table. That's going to take up several board feet. Do we have enough board feet right now? Or do I got to send him to Home Depot and beg his parents to fund the project?”

Beginner students regularly make mistakes that waste lumber, but the classroom should be the time and place to make errors, he said.

Yet Weissman’s school already charges $25 for an eight-to-10 week shop class, a fact that pains him. Paying out of pocket for wood may not be an option for many students at the school, which has half of its students depending on free and reduced lunch programs.

As Sommerfeld transitioned to his new role, he found carpenters and builders who tossed excess materials in landfills. A connection via a social studies teacher got leftover pieces from stair stringers. Now, he makes regular pickups from several contractors, who can write off the two-by-fours and six-by-tens as charitable donations.

A shrinking profession

“Here's a scary thought,” Sommerfeld said. “Since I've left the school, they can't find an instructor certified to teach those classes, so there is a large chance that this coming school year, no one's going be teaching woodworking or construction or engineering or robotics at that school.”

The number of workers who have gone into the trades has dwindled over the last several decades. Even fewer have the skills or desire to teach.

Weissman said he’s seen his shop teacher colleagues in high demand across the Midwest. Nevertheless, many roles go unfilled, and programs shutter.

At the same time, local contractors knock on shop teachers’ doors, desperate for potential workers who display even basic interest in the trades.

Veronica Medina, a former student of Sommerfeld’s, is the daughter of parents who both studied architecture. That steered her toward the trades. First, she pursued architecture at the University of Wyoming, but found it wasn’t her path.

Instead, she attended community college, and used some of the skills she’d learned before — both from class and from her parents — to show she knew what she was talking about in job interviews. Today, she works designing custom cabinets.

The path there wasn’t a straight line, but Sommerfeld — who Medina described as her favorite teacher — helped her discover that failing is just discovering a method that didn’t work.

“He's a great teacher to be able to fail and not feel like a failure,” she said.

As shop classrooms dwindle across the country, Weissman and Sommerfeld say it's time to get in front of kids earlier and more often.

“We need to get elementary school kids on construction sites,” Weissman said. “We need to get middle school kids interviewing construction workers.”

Sommerfeld said a paradigm shift is also vital to “rebuilding.”

“How do you do that?” he said. “Well, you build from the ground up by educating the people and giving them the skills. They need to do that. And it's so worthwhile.”