Building information modeling (BIM) has been creating project efficiencies from the moment designers began using its earliest renditions in the 1980s. Since then, the technology has been used in the design and construction of buildings, bridges and many other structures.

And there’s still plenty of room to grow. In fact, Allied Market Research reported that the BIM industry is expected to achieve a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 21.6% from 2016 to 2022 and earn $11.7 billion by the end of that period.

In addition to a large number of construction and design companies in the U.S., firms around the world have embraced the technology as a way to achieve financial and time savings on construction projects and to share information using the same format.

The United Kingdom, Russia and other European countries are in various stages of implementing BIM standards and mandates for those contractors that want to do business with their governments. U.K. firms have realized 15% to 20% construction cost savings from 2009 to 2015 by using BIM.

For the U.S., Jim Lynch, vice president of Autodesk's construction products line, wrote in The Hill, a political publication, that kind of payoff could mean enough extra money to fix all the nation's structurally deficient bridges — with $175 billion to spare. In its most recent data release, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the seasonally adjusted annual rate of public construction spending at the end of October was almost $292 million, so the implications are clear.

No U.S. standard in sight

Experts believe BIM could save a significant amount of money if public agencies in the U.S. develop a common set of BIM standards and require construction companies and designers that want to do business with them to use it.

Additionally, said David Crane, vice president of government affairs and senior corporate counsel at Autodesk, America leads in BIM technology use. You’d be hard-pressed to find a contractor or an architect who isn’t familiar with Autodesk’s Revit or BIM 360 software tools. “We've got the hardware and connectivity and tools like iPads,” he said. "It’s all U.S. products that can digitize the construction cycle.”

But a U.S. BIM standard won't materialize — at least for the foreseeable future. “There isn’t a prescribed structure for [a common set of government practices],” said Roger Grant, program director at the National Institute of Building Sciences (NIBS). “We don’t have one agency responsible for all construction like the U.K.”

The nonprofit NIBS was established to serve as a go-between for the private and public sectors in order to advance building science and technology to improve the built environment, but Grant said it’s a challenge to get alignment between agencies and industries that have their own ways of operating.

Adam Matthews, chief of the EU BIM Task Group, said agencies that believe they have too many unique challenges to effectively collaborate on BIM might be doing themselves a disservice. “When we come to this conversation, we think we’re different, but we have much in common,” he said. Once organizations realize that construction works pretty much the same worldwide, Matthews said, it will be easier to get unanimity, even among countries.

Local BIM mandates

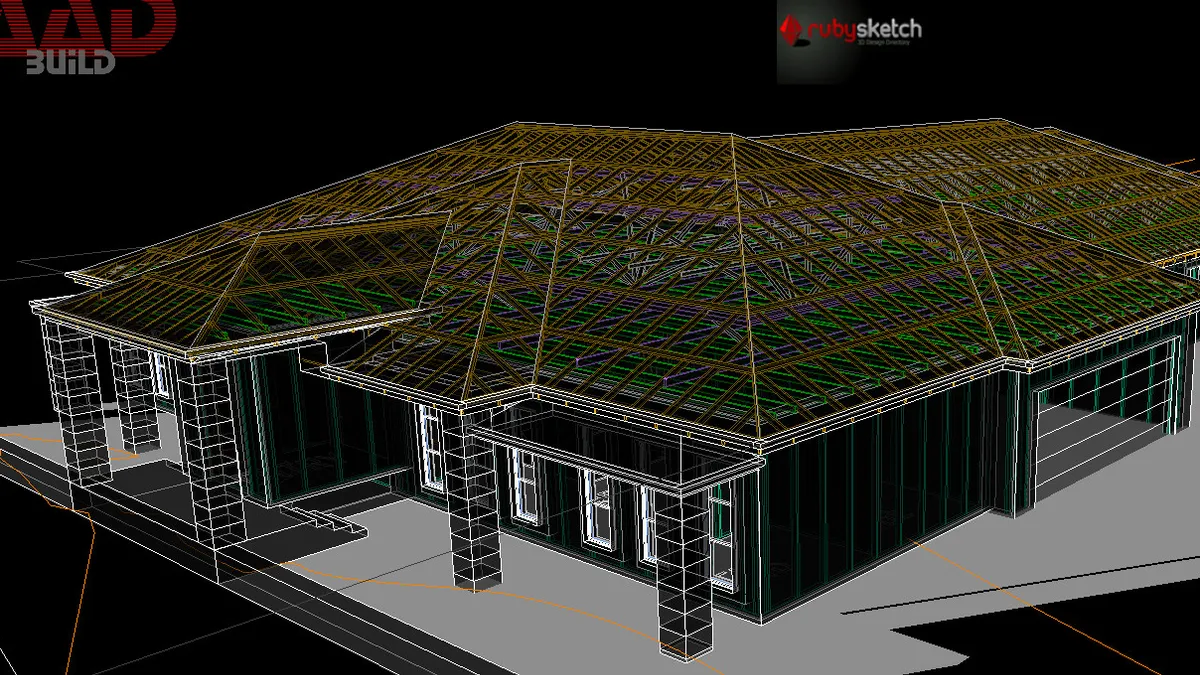

Though there isn't a national BIM directive, there are BIM mandates in the U.S. in places like New York City and Broward County, FL, said Russ Dalton, global BIM director for the Americas at AECOM. “What [BIM] does for us is it allows us to build it virtually, so every brick and stick is in the model,” Dalton said. “When we build, we can get it done quicker, leaner and operate it with greater efficiency.” However, some agencies that require contractors to use BIM, he said, might not oversee the firms' BIM use well enough.

Grant said federal agencies, like the Army Corp. of Engineers and the General Services Administration, that want their contractors to use BIM have developed mostly independent programs, partly based on funding. “If there isn’t [building] activity, there probably isn’t going to be a lot of development of [standard practices],” he said. For example, the NIBS official said if funding for courthouses increases, then that would likely drive more BIM-based development in that area.

But those agencies that are working on their own BIM policies and procedures do have an informal network through which they share information and collaborate. “Agencies are doing as much as anyone in the U.S. to advance standards and common practices,” Grant said. “That’s not their main objective, but it is an outcome of improving operations.”

While Dalton has seen the benefits, he said the real driver of BIM's growth will be how much money owners can save by using it in conjunction with building operations and maintenance. “For every dollar spent on design and construction,” he said, “eight dollars will be spent on operations and maintenance.” The realization of significant savings, he added, should cause a natural migration toward BIM.

And size doesn’t matter when it comes to BIM. Dalton said most smaller companies have the resources to implement the technology, but their hesitation comes from having to adjust to new processes. “A lot of people don’t want to change,” he said.

Millennials might force that shift, however. Dalton said the younger generation of construction industry workers is demanding that technology and drawing older professionals on board. That's because it provides a way to shorten the learning curve by allowing inexperienced workers to get the same “big picture” understanding that it took previous generations a whole career to attain.

BIM's infrastructure benefits

In an impassioned plea in The Hill, Lynch aimed at lawmakers who will soon be reviewing President Donald Trump’s plan for a $1 trillion infrastructure initiative. Lynch laid out the benefits of incorporating BIM into the plan and being able to build a project first on a computer screen, eliminating conflicts and questions before they become expensive and time-consuming fixes out in the field.

These advantages are particularly compelling when the conversation turns to projects like Trump's infrastructure initiative, which is expected to require at least a $200 billion direct federal spend.

But as the unveiling of the White House infrastructure plan draws near, there are a few key BIM-related questions that policymakers must address. Two key questions are how is the nation going to best use its dollars and resources, and how will BIM fit into that equation?