Last month, U.S. businesses got a moment of clarity on what may be the most important workplace storyline of 2021.

On Dec. 16, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) all but confirmed that employers may require proof that employees have a received a COVID-19 vaccination without violating non-discrimination laws such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), stating that such mandates are not ADA-defined medical exams in and of themselves. Though the agency did outline some exceptions, employment law experts say the guidance will be of use to employers.

At the same time, EEOC did not outright sign off on employer's vaccines mandates altogether. "It wasn't as clear as you would expect," Jason Habinsky, partner at Haynes and Boone and chair of the firm's labor and employment practice group, said of the guidance. Habinsky's takeaway is that EEOC is saying "in certain circumstances you can require it, but if you do, here are some things to keep in mind."

The guidance also leaves out certain information on how a vaccine mandate might impact certain classes of workers, including pregnant workers and workers under age 18. These are just a few examples of an area in which employers may have more questions than answers.

#1: Could a mandate's exceptions 'swallow the rule?'

The EEOC's guidance outlines specific information about how vaccine mandates intersect with the ADA, Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act. It makes clear that employers may need to exempt from mandates workers who cannot receive the vaccine because of a disability or a sincerely held religious belief — although they may then be excluded from the workplace in some circumstances, according to the guidance. However, there are at least two additional subsets of workers whom employers may need to keep in mind as they determine how to handle vaccination policies.

Pregnant workers are one such group, and they are protected both by the federal Pregnancy Discrimination Act as well as various state and local laws, Habinsky said. He noted that EEO law requires employers to provide reasonable accommodations to employees who are pregnant for any disabilities or medical issues related to their pregnancies.

"If a pregnant employee states that, due to her pregnancy, her healthcare provider has advised her not to receive the vaccine, the employer should treat that situation the same way it would treat any other request for accommodation based on a medical condition," Brett Coburn, partner at Alston & Bird, told Construction Dive sister publication HR Dive in an email. Essentially, the employer can consider the request and conduct an individualized assessment to determine how to respond, he added.

Younger employees are another group that may be exempt. That's because the COVID-19 vaccine developed by Pfizer and BioNTech has been recommended for persons 16 years of age and older by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). On Dec. 18, the CDC announced that a second vaccine, developed by Moderna, received emergency use authorization for individuals 18 years of age and older.

Employers can expect to see clinical studies that deal with individuals under the age of 16, said Barry Hartstein, shareholder at Littler Mendelson and co-chair of the firm's EEO and diversity practice group. But in the meantime, those who employ such workers "need to be mindful" of continuing to engage in existing protocols and conducting frequent COVID-19 testing for these workers, Hartstein said.

Taken together, it's clear that a number of broad groups may be exempt from a straightforward mandate. That alone could cause employers to think twice about instituting such policies.

"Right now, the question you have to ask yourself is, could the exceptions swallow the rule?" said Hartstein. "Our goal should be as employers to do everything we can to limit the spread of the virus and keep people safe."

#2: Is the current stage of vaccination conducive to a mandate?

Current vaccination programs are operating under the Food and Drug Administration's Emergency Use Authorization authority. To date, two vaccines — the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine and the Moderna vaccine — have received emergency use authorization.

That authorization essentially means both vaccines are still in the experimental stage and have not received the FDA's full approval, Hartstein said. The vaccines are being rolled out in stages on the state level, he added, starting in large part with healthcare institutions, many of which have taken the position that they will not mandate vaccination until the FDA grants full approval.

Furthermore, a fact sheet given to patients who receive a vaccine discloses that they may have an allergic reaction to the vaccine, which is something employers may need to note in their planning process, Hartstein said. A sample fact sheet for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine has been made electronically available by the companies.

So far, early reports from state governors make it apparent that employers will face hurdles to adopting a mandate, even if they operate in industries deemed essential. During a Dec. 17 U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation webinar, Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson said the state's first shipment of vaccines prioritized healthcare workers and went to hospitals and pharmacies, while residents and staff in long-term care facilities are next in line.

When asked about vaccinations for essential workers, however, Hutchinson said this "could be a little more challenging," adding that the current supply of vaccines in Arkansas was not enough to cover the state's total population of essential workers.

Determining how to allocate Arkansas' first shipment of vaccines was "easy," Hutchinson said, but "as you get more and more vaccines into the supply chain, there's going to be increasing scrutiny and debate as to how that's going to be allocated."

The U.S. has the capacity to complete between 100 million and 150 million vaccinations per month, though most people will need more than one dose, Dr. Troyen Brennan, executive vice president and chief medical officer at CVS Health, said during the webinar. He added that vaccinations could begin for essential workers by mid-to-late February 2021. "There's no reason why this can't go relatively rapidly," Brennan said.

That prediction comes amid news that hospitals in several states are getting 25% to 40% fewer COVID-19 vaccine doses during the week of Dec. 20 than expected, Axios reported.

As the status of the rollout progresses, employers that are considering a vaccine mandate need to be mindful of how widespread and accessible a vaccine is, Habinsky said.

#3: Should workers be given paid time off to receive a vaccine? How about incentives?

Incentivizing employees to receive a vaccine is "critical," Habinsky said, and providing paid time off to receive a vaccine could be one way of doing so.

Providing PTO to recover from side effects "is certainly a good idea" and may be required under some state and local laws, said Coburn. Per the CDC, side effects of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine may include pain, swelling and redness in the arm in which patients receive the shot, as well as chills, tiredness and headaches. "For employees who have exhausted their PTO or paid sick leave, employers may wish to consider providing additional PTO for this reason, but they will have to balance this potential incentive against the potential for abuse by employees who get a vaccine and then use that as a reason to get a day or two of paid leave even if they are not suffering side effects," Coburn added. Employers also may need to stagger employee vaccination dates to ensure sufficient coverage at work.

Another option — and something that may be an alternative to a vaccine mandate altogether — is a more direct incentive. Employers have long used wellness plans to provide employees cash awards focused on both health outcomes and health-related activities, Steven J. Friedman, shareholder at Littler Mendelson, said in an email to HR Dive, but a vaccination incentive "would not be an outcome or activity based reward."

Instead, a vaccination incentive "would be considered a participation-based award provided outside of a health plan and as such, EEOC rules would govern," Friedman said. EEOC regulations on participation-based wellness programs specify that employers must provide a reasonable accommodation to employees with disabilities to ensure such employees may participate. If an accommodation is not available, the regs provide that a reasonable alternative to the activity must be available so that employees can still earn the award without participating in the activity.

"In the case of vaccination, it is not yet clear what all of the issues may be in connection with either accommodating employees or finding reasonable alternatives for those who are not able to be vaccinated," Friedman said. "However, it would be possible to predict that, based on preliminary finding, certain individuals may be allergic to a vaccine and cannot be vaccinated safely. In this instance, an employer may need to permit these employees to engage in another activity to receive the wellness award."

But it is still unclear how the EEOC regs would apply to a situation in which an employee objects to receiving a vaccine on the basis of religious practice or personal objections, according to Friedman. "Presumably, if the objection could not be defined as having a relationship to a disability, there need not be any accommodation or alternative provided," he said, speaking about wellness programs with incentives.

Incentives may also appeal to employers worried that a significant portion of their workforce may refuse to comply with a vaccine mandate, Coburn said, because such a mandate could put employers in the position of having to either terminate those employees or deviate from the mandate.

Employers can also encourage employees to receive a vaccine by running education campaigns and covering any costs associated with getting a vaccine, Coburn added. Habinsky noted employers may be able to work with their health plans to provide coverage for any costs associated with being vaccinated.

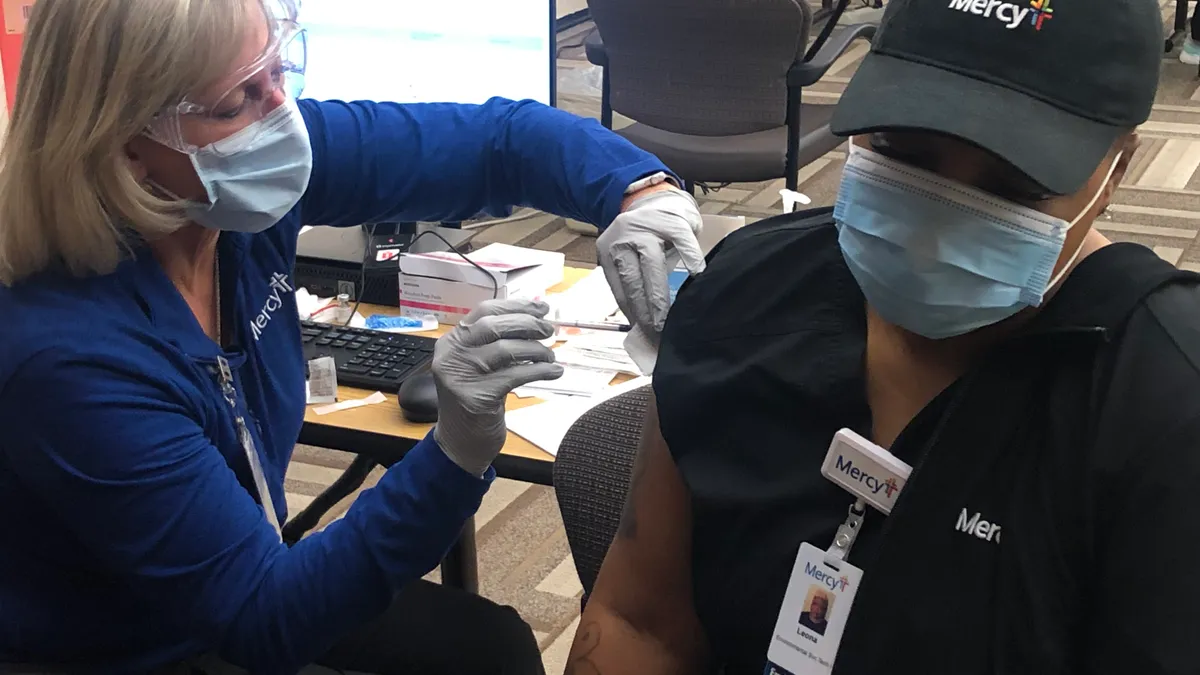

Marketing can be just as important as incentives to employers seeking to encourage vaccination, Hartstein said. For example, he recommended that employers consider taking photos of their CEOs receiving a vaccine so as to encourage the notion that the vaccine is safe and effective.

#4: What if a group of employees refuses to be vaccinated?

In a previous interview with HR Dive, Hartstein noted that employers may have compliance concerns with respect to the National Labor Relations Act when issuing vaccine mandates. If a group of employees protest COVID-19 vaccination, that may enter the territory of protected concerted activity, he said.

On the flip side, those operating in workplaces with unions might want to consider involving their union representatives. "If you want a vaccination program to be successful, there's always to be a question of whether or not you have a duty to bargain with the union before you roll it out," Hartstein said. "It really is important to include your union representatives in the conversation."

Employers may also need to be aware of any guidance on vaccinations published by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. The OSH Act's general duty clause specifies that employers must provide "a place of employment … free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm" to employees.

But there's a question as to whether the employer should maintain a safe and healthy workplace by requiring a COVID-19 vaccination, said Habinsky, and OSHA has yet to publish specific guidance on the matter.

#5: How might things change as the vaccine becomes more widely available?

Ultimately, the availability of a vaccine will factor heavily in determining to what extent employers may be able to mandate vaccination, Habinsky said.

Should vaccines become widely available in the next few months, employers may need to prepare for a rush of employees trying to be vaccinated at the same time, said Coburn. And if a number of employees need to take time off to deal with side effects, this could put pressure on staffing levels.

Vaccines are not the "be all end all" of an employer's COVID-19 response, Hartstein said. It's unknown whether those who are vaccinated may still spread the coronavirus asymptomatically in the workplace, meaning precautions such as mask-wearing and social distancing should still be continued moving forward.

The vaccine is merely one more arrow in employers' quiver, Hartstein said. It's "one more way that we can try to bring us back to normal as quickly as we can."