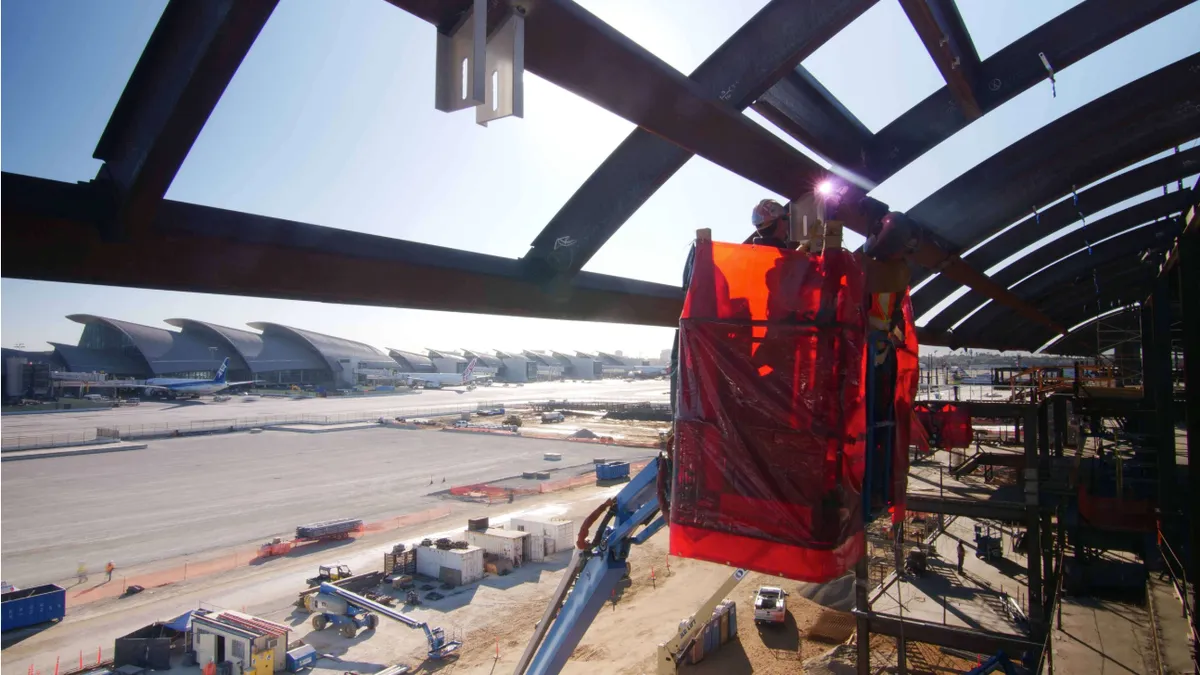

The $1 million a day, 1 million square-foot Midfield Satellite Concourse expansion of the Los Angeles International Airport is on schedule to open next year. With more than 1,000 workers and 300-plus salaried staff powering the progressive design-build strategy, how does this “beast” of a project stay fed?

Two factors keep the $1.6 billion monster satisfied while still adhering to its budget, said a team of executives at an AEC Next conference session in Anaheim, California, last week: collaboration and technology.

An owner’s rep from the Los Angeles World Airports (LAWA) authority, two architects from Corgan and a manager from joint venture contractor Turner-PCL Construction shared specific benefits and challenges of the 5-year-long project, touting the merits of co-location and of using laser scans, AR/VR, BIM and smart glasses to keep the massive job on schedule.

The Taj Mahal of trailers

“When you have 1,200 folks on site, one little thing can send the whole crew home,” said Terry Brickman, construction quality manager for Turner-PCL. “If you're feeding a monster, as I call it, you have to keep it fed.”

As is often the case with progressive design-build — a project delivery method that LAWA hadn’t used before, but said it needed in order to keep pace with ferocious growth in aviation demand — contractors “were digging before we had final structural design,” Brickman continued. “And so it was critical to be able to, if we had an issue in the field, quickly pull together the designer and the owner and say, ‘What are we gonna do here as a team?’ You could never do that in a traditional setting.”

With teams of architects, engineers, owners, project managers and trade contractors set up in adjacent trailers in what the team refers to as their Taj Mahal, or trailer city, stakeholders with answers to another party's conundrums are never more than a few cubicles or a breakout room away, said Monica Sosa, a project manager with lead architect Corgan.

The teams don't stop at co-mingling at trailer city, walking from one cube to the next to get the answers or advice they need when they need it. The DB team holds events off the jobsite, getting to know one another to strengthen their communication and bonds. “You have to relieve the pressure some place,” Brickman quipped. “And it was really fun to do that at the bowling alley throwing a ball,” for example.

Workshops held at the trailers help keep different teams abreast of the needs of structural, mechanical or electrical trades, for instance, and local government, airline representatives and peer reviewers are able to drop-in to the one-stop nucleus of the project.

BIM for the win

For successful quality control on a project this size, Brickman said the team came up with key performance indicators to measure the health of the project. "At any given time, [a dashboard] was open to all of the executive teams from all the groups that could look at it and find exactly what's going on on the project in any particular KPI,” using primarily BlueBeam color-coding markup software.

“We had over 9,000 comments on design components alone that we had to make sure we tracked and measured and wrestled to the conclusion to make sure we build the product that the owners are looking for,” he continued.

Peer reviewers and some other key stakeholders — including more than 30 entities from all over the world, such as consultants and finishing artists — couldn’t be on site at all times, but that didn’t stop them from remotely reviewing progress being made in the field.

Through 3D scans captured by the Matterport Pro 2 depth sensing camera, for example, the team was able to identify a crack in the utilidor slab and propose an epoxy injection fix, noted Corgan architect David Huor. "We were able to scan and send the link off to the structural consultant, who was able to review and approve [the fix] without ever having to come on site.” The Matterport system overlays geometric information with images taken by the camera, Huor explained.

Airport officials were also able to strap on a virtual reality headset with a view of Autodesk's Revit and Navisworks modeling software and other tools that allowed them to check critical components of the final design. For example, they previewed the visual clearance of airplane tails from what would be the facility's first-ever ramp control tower that the airport — not the FAA — would be controlling.

The team had to manage 74 Revit models and more than 100 AutoCAD files used by civil engineers. When the project started in 2015, the load was enough to crash the team’s servers on a daily or weekly basis early on, Sosa admitted. The team worked with Autodesk through early growing pains to fix bugs and streamline the workflow, which they managed through a file system on the BIM 360 platform.

As another benefit of design-build, Brickman continued, MEP subcontractors also had access to the team’s BIM models, and all shared their integrated conduit, electrical and plumbing models for clash detection. “It was all great on the computer,” he continued. “But what really drove it was in the field,” where the teams could make sure that conduits were in the correct location before pouring concrete floors, for example.

“[The owner] also asked me one day how I know that a 24-foot-tall tower in the new terminal is within tolerance,” he continued. “I said, ‘That’s a really good question.’” Brickman’s team conducted point cloud scanning of the walls in the basement, set a tolerance level based on ACI standards and reviewed a topographic map to ensure it was within tolerance, which he says may have been impossible or incredibly difficult without those tools. “Using technology in the field is very advantageous,” he said. “I owe [LAWA] a new building, not a jack-hammered-up building, so we have to get it right the first time.”

Remote-control quality control

Another boon to the delivery of the project and quality control aspects has been augmented reality, Sosa continued, and that came particularly in the form of remote mentorship through Daqri smart glasses technology.

Remote mentorship involves having an architect, for example Sosa, walk the site with the glasses on to analyze as-built conditions while another collaborator such as Huor sits at a computer in the office. Whatever Sosa looks at, Huor can see, and can interact with — sketching on the screen for example, to point out issues or design changes to Sosa in real-time in her physical line of vision while they speak.

Sosa could also use the glasses to overlay BIM models on the physical environment and tag issues that she sees, which will then live in the model to be addressed by the appropriate party.

This was a great feature, Brickman said, because when you have 749 outstanding issues after spending more than $800 million, quality managers need to know where to focus their attention. The issues are also posted on weatherproof QR codes throughout the facility's more than 800 different rooms. Field workers can scan these with iPads and filter by area or type of issue, for example, to get insight on a problem they're tackling.

“This is the type of collaboration that [LAWA] was looking for, that would allow the owner, designers and contractor to work together toward conscious solutions so we can really make a great building,” David Kim, an architect representing LAWA, explained.

On a project of this size, “you can’t take a subcontractor by the hand and walk them through all of these issues,” Brickman continued. “You have you find an efficient means of technology that will allow them to keep moving.”

Evolving with market forces

As stakeholders aim to keep the expansion on budget through its projected completion in the summer of 2020, they've had to overcome a number of challenges. One of the biggest, Kim said, were change orders stemming from aviation market forces that bumped the project up from 12 gates to 15 gates. “We’re working through that,” he said. “Even with that, we’re coming in on time and budget.”

Access on the site has been somewhat tricky as well, given FAA security protocols on airfields and having to manage 1,200 workers coming in and out at any given time, Kim continued.

“Putting $1 million of heavy construction in place every day for a few weeks is hard, but to do it every day for three years is very, very difficult,” Brickman added. One of the biggest drawbacks so far, Sosa said, was that the team didn’t implement some of the technology they are using today sooner. That’s because the tech market has changed quite a bit in the past five years, she noted, and so some of what’s being used today wasn’t even available when the project started.

And a lot may still change in the next year, Sosa concluded. For example, the team's AR glasses currently are limited in their ability to overlay and integrate multiple systems such as structural and electrical, she said, but that could change in no time, paving the way for new efficiencies before the project wraps up.