This feature is a part of "The Dotted Line" series, which takes an in-depth look at the complex legal landscape of the construction industry. To view the entire series, click here.

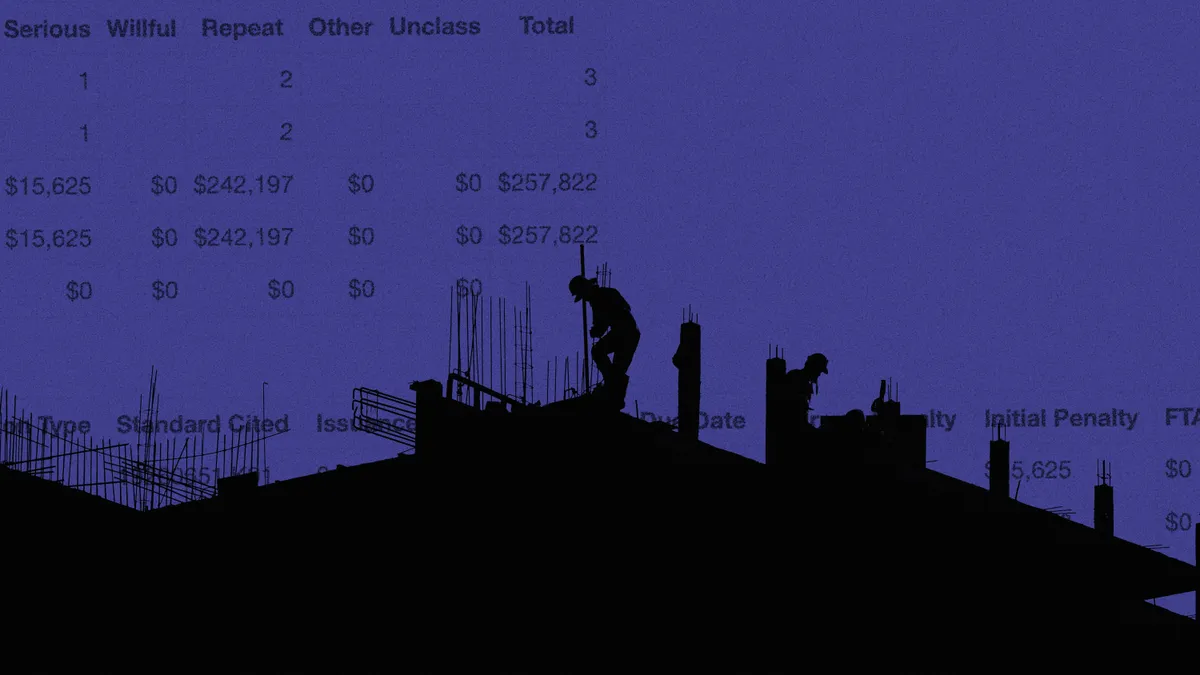

The U.S. government appropriated $120 billion for federal construction spending in 2017, covering a range of projects from the construction of a new Federal Bureau of Investigation headquarters to building agricultural research facilities, according to the Associated General Contractors of America. President Donald Trump's 2018 budget proposal, even with its cuts to key federal spending programs and new funds for a U.S.–Mexico border wall, calls for roughly the same level of investment.

Because of the potential for a big payoff, some companies have elected to become experts in the federal contracting field, making it the focal point of their business plans. Other contractors, like international design, engineering and construction firm AECOM, have set up specialized business units to take advantage of government contracting opportunities.

Government contracting is also the path to prosperity for many construction companies owned by women, veterans, minorities and other economically disadvantaged entrepreneurs because most federally funded projects have participation requirements, and all states, plus Washington, DC, and Puerto Rico, have instituted some versions of these regulations as well.

Playing by the rules

It’s not all upside, however. There are several special rules that go hand-in-hand with doing business with the federal government, and the consequences for running afoul of those regulations can be serious — including suspension or debarment from bidding on future public work.

For federal work, it all starts with the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR), or Title 48 of the Code of Federal Regulations. FAR is where one can find the procurement rules for almost any federal agency. State agencies have their own regulations about buying goods and services.

Diverting money meant for subcontractors and material suppliers, misleading a government agency about what role minority firms play on the project, billing for defective work — a possible violation under the False Claims Act — or billing for work that isn't complete are just a few ways contractors could be kept out of the federal procurement game, said Lee Weintraub, vice chair of the construction law and litigation practice group at the Fort Lauderdale, FL–based Becker & Poliakoff.

Regulations can even keep a construction company from bidding on its first project. “Bid forms will ask you if you’ve ever been defaulted by an owner — that could blackball you," Weintraub said.

Understanding suspension and debarment

It’s only what happens after a contractor has signed on the dotted line that suspension or debarment is possible.

Steve Sorett, an attorney at Kutak Rock, in Washington, DC, said suspension usually occurs when an indictment is handed down against the company or one of its owners or another urgent circumstance arises, throwing into question the company’s ability to finish the project responsibly. According to the General Services Administration, a suspension lasts as long as it takes the government to conduct an investigation, or up to 12 months.

“Suspension is a protective device for the government,” Sorett said. “[The government is saying], ‘We have a hot issue and have to deal with it right now.’”

Debarment, however, is a process through which the government seeks to have a contractor banned from bidding on work and possibly removed from existing jobs for a set period of time, usually three years.

One of the most common causes of debarment that Erik Ortmann, a Woodbury, NY–based partner at Kaufman Dolowich & Voluck, has seen is a violation of prevailing wage laws. Not paying the required minimum wage — or worse, falsifying certified payroll records to reflect the proper amounts — can lead to debarment or at least an investigation by the governing authority.

Companies aren’t always trying to circumvent the prevailing wage requirement when they find that they’ve violated it. “There’s just confusion on what they’re supposed to pay,” Ortmann said. However, he added, the cases that make it to a debarment proceeding or suspension are typically willful in nature.

Federal debarment today will also lead a contractor to state debarment in many jurisdictions because so many local and state agencies consider that to be a disqualifying event. “You’re effectively on the sidelines during a debarment period,” Ortmann said.

Debarment is meant to be a deterrent and not a punishment, said Robert Wagman Jr., a Washington, DC–based partner at law firm Bracewell. But many times it’s viewed that way. There has also been an uptick in enforcement, something federal agencies can use strategically to demonstrate to Congress that they don’t need to increase oversight of their federal contracting programs.

Ethical crisis management

The fallout from being debarred can be disastrous. “If it’s a small part of your business, you can survive it and move on,” Wagman said. However, he isn't aware of any companies that have come back from debarment and are looked at in the same way — that is, as beyond reproach — as they were before.

That's one reason businesses devoted to federal contracting take ethics and compliance seriously and are quick to react to a problem, he said.

Some of the actions contractors can take to resolve a suspension, for example, as well as to prevent debarment, are to remove the people that were behind illegal or noncompliant actions from the company or put them in an area of operations where they don’t have the same kind of responsibility. Debarment, Wagman said, is discretionary, so there are ways to settle the charges with the government and demonstrate that the company is worthy of a second chance as a government contractor in good standing.

The best strategy is to avoid the circumstances that would warrant suspension or debarment in the first place.

According to Sorett, contractors should take the following steps to protect themselves against situations where they could run astray of federal contracting rules.

1. Establish or strengthen compliance programs

A thorough review of policies and procedures is critical when hiring employees and engaging independent contractors and subcontractors to ensure that federal, state and local laws are being followed. Subcontract documents should include flowdown FAR clauses so that subs at all tiers must also follow them, Sorett said. All of these policies should be reviewed periodically, he said, and annual training should be offered to both employees and subs on the subjects of business ethics and FAR compliance. Random audits round out the program.

2. Create a crisis management program

Develop an action plan to respond to any charges of violation of federal contracting laws and that can be executed quickly in the event of an ethics or compliance problem. “Being caught flat-footed and not prepared for crisis management is never a good thing,” Sorett said.

3. Run all employees through the E-Verify system

E-Verify is an online system that lets employers working on federal projects check the employment eligibility of their employees. “In this current environment, be sure to have an E-Verify program in place and actively manage it to avoid immigration or customs problems," Sorett said.

4. Comply with Buy America regulations

Be cognizant of all Buy America compliance requirements when purchasing supplies and equipment.

Internal checks and compliance are critical because it’s hard to bounce back from a debarment. “There’s a very small grapevine in the public construction space, and word gets around,” Weintraub said.

The Dotted Line series is brought to you by AIA Contract Documents®, a recognized leader in design and construction contracts. To learn more about their 200+ contracts, and to access free resources, visit their website here. AIA Contract Documents has no influence over Construction Dive's coverage within the articles, and content does not reflect the views or opinions of The American Institute of Architects, AIA Contract Documents or its employees.